How young the Faces on this day |

The Presidents Son 7-12-1944 |

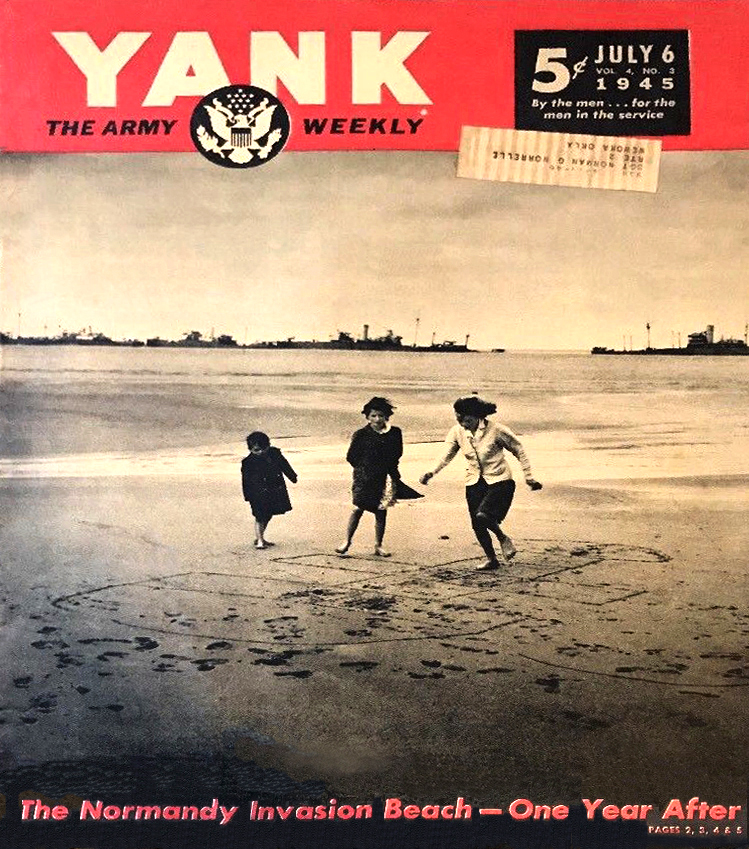

From “YANK” Weekly Magazine

July 6, 1945 (Vol. 4. No. 3) by Sgt. Dewitt Gilpin

“YANK” Staff Correspondent

OMAHA BEACH, NORMANDY—Only the sun and the wind now rake the long beaches of Normandy, and kids with toy shovels play in the sands, where a year ago great armies came by sea.

From scarred pillboxes silent coastal guns point aimlessly down the beaches that on June 6, 1944, were covered with dead Americans. A year has passed and the beaches where the invading armies landed are quiet now.

In front of Omaha Beach are the rusted hulls of ships sunk by the Allies themselves to make a breakwater. Some day the Navy will come and salvage the ships. In the meantime, two rammed-together freighters close to the shore are used as a rendezvous by couples at night.

Fisherman and peasants in need of fuel have dismantled most of the shattered beachside houses that the Germans used for emplacements. But in back of Omaha Beach the brick chateau with its tiny Norman towers still stands. And the faded inscription written on the chateau by a doughboy long ago attests to the fighting that occurred there. The inscription states: “This ain’t no USO.”

Stretching away from the beaches are green fields and apple trees, lush and inviting. No one goes into these fields. There are signs which read: “Achtung! Minen.” (Attention! Mines)

German soldiers still walk along the beaches which they once defended. But now these soldiers are prisoners and they cut sod for the cemeteries where Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair and Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt rest with their men.

In two-wheeled carts drawn by gaunt horses, the people of Normandy come to the beaches on Sunday afternoon. Fathers explain to their children how the shell-twisted landing craft were used.

When men and women speak of the fighting on the beaches, they speak quietly. They recall that it was from these beaches that the long march started – the march that ended 11 months and two days later, May 8, 1945.

People point to the twisted landing craft, the bent pillboxes, the hushed cemeteries in the distance, and they tell again the story of the armies that come from the sea and fought on the beaches. Now children slide down bomb craters, where grass is beginning to grow.

How young the Faces on this day |

The Presidents Son 7-12-1944 |

There are a few veterans from the D-Day divisions now stationed around the little coastal towns of Colleville, St. Laurent, Vierville, Bayeux, Carentan, Varouville and Ste. Mere Eglise. They remember D-Day with the limited perspective of soldiers who could only see what happened around them. They were, it is true, briefed on the “big picture.” But to most of them, it is all hazy now.

These invasion veterans are now MP units and they patrol the coast they helped liberate. They left their combat units because of wounds or combat exhaustion following the landings; one MP’s eyebrows turned white in the hospital; another MP speaks with a stutter that followed a wound and concussion. Some of the men have gone back to the beach and laboriously reconstructed their route and plotted the spots where buddies were killed. Others haven’t bothered because they would rather forget.

D-Day’s big picture, as relived on the situation map, went as follows: After the terrific naval and air bombardment, the 4th Division, supported by elements of the 90th Division, landed at Utah on a strip of beach behind which lies St. Mere Eglise, St. Martin du Mont and Varouville.

Already ashore and waiting for the seaborne infantry was the 82nd Airborne Division. To the left of this beachhead on the V-shaped coast, the 1st and 29th Divisions made their landings between Colleville and Vierville. Already ashore in front of them was the 101st Airborne. Sandwiched between the two beachheads were the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions who scaled the cliffs near Point du Hoc to attack six coastal guns. Further to the left on the coast in front of Caen, the Canadian and British made their three beachheads.

A model dressed as an Airborne Paratrooper hangs from the cathedral steeple by the shrouds of his parachute. In real life he did receive a bullet wound to his foot or leg as he watched the attack continue to play out below him. He was rescued when other troopers entered the cathedral and his wounds treated. His name was John Steele, Airborne Paratrooper, rank unknown. This moment was depicted in the movie “The Longest Day” 1962 by Twentieth Century Fox Studios, Hollywood by the Actor, Red Buttons. Location: St. Mere Eglise, France, inland from the beach landings taking place a short distance away.

Once astride the beaches, the Americans troops jumped off from the beachheads at each end of the V-shaped coast and drove towards the base of the V, effecting a juncture near Carentan. Control of this strip of coast and the road network within it, set the stage for sealing off the Cherbourg peninsula and the push on to St. Lo.

Cpl. Fred Clausen of Salinas, Calif., is now stationed on the sea at Carentan, which is about 10 miles from where he came down in a swamp with four other troopers from the 101st Airborne.

He wasn’t particularly scared. The worst thing was sweating out the C-47 which was set afire by ack-ack while still over the sea. He jumped while still over water and the drift carried him and his four buddies forward into the waist-deep water that the Germans had flooded onto the fields adjoining the beach. He never found out what happened to the other paratroopers on the plane.

Naval guns were shelling the area where the men came down and they were more afraid of our shells than the Germans. After shooting their way through a German ack-ack crew, the troops holed up in the farmhouse of the Jules Bourdet family, who then as now boarded a pretty schoolteacher, Mademoiselle Barbier. Between the troopers’ forays out to cut German communication wires, the schoolteacher taught Clausen his first words of French and he still goes back to see her “ever so often.”

“On the fourth day,” Clausen says, “I saw one of our tanks coming up the road and it made me feel good. Then I saw his gun go off and wondered who he was shooting at. A second later I knew; the bastard had nicked me in the leg with a piece of his shell. So we hunted around until we found some rangers who knew what paratroopers looked like.”

The first juncture with the 82nd Airborne was made by the 4th Division from its Utah beachhead. Coming in with the 2nd Battalion of the 8th Infantry was S/Sgt. Walter A. Janicki of Pittsburgh, Pa. He is a short, husky GI who used to work at a Jones & Laughlin blast furnace.

The 88s were still whooming in when Janicki hit the beach and Machine Gun fire was raking their positions. He was a bazooka man then and he had a job to do.

“I missed the pillbox with my first shell,” he recalls. “But I got the sonubabitch with my second. I can take you down to the beach and show you where it was if you want to go.”

After cleaning up the coastal pillboxes, Janicki’s battalion pushed down a secondary coastal road and joined up with the 82nd near Varouville.

“One thing I’ll never forget about the beach,” Janicki says, “is going back to get a buddy I knew had been hit. It was after I got the pillbox. But I don’t want you to print who he was or how he looked. An 88 had hit him bad. “But you can print that I’ve lost half of my hair. I’m not like some of the guys about things like that. And I stutter now too! But I’m not ashamed of it”. And that you can print!”

Men and Equipment stream onto the secured beachhead . Many more ships await their turn to beach and unload their cargo and the reinforcements for the units now advancing inland. Supplies that are badly needed at the front line must flow like a never ending river.

For Janicki and the men on Utah beach the invasion went pretty much by the book; on Omaha they had to throw the book away and get ashore through the guts of men who made a beachhead. Everything went wrong from the weather, to the fact that the Germans had an extra unexpected division looking down their throats when the first thin waves of Yanks staggered from a sea filled with sinking boats and drowning men.

Pfc. Herbert H. Adams is a drawling, six-foot Texan who landed with B Company of the 2nd Ranger Battalion on the right of the 29th and 1st Division units. In England the special training given the rangers had prepared him physically for the ordeal on the beach; his body kept going and carried him through it, but there are some blank spots in his memory on those things that people like to read about after the battle is over.

He knows that his company lost 11 killed and 24 wounded out of 68 men before they got off the beach, because an officer told him so later. He remembers the explosion when his boat hit a mine, and he remembers the relief that he felt when he found that his gas mask kept him afloat. Then he was firing at the slots in a pillbox and pretty soon he was going up a road with a sergeant who was walking on an ankle with a bullet hole through it. Somewhere along the road the sergeant was hit, and it was days later before they finally got to the other Rangers who had been cut off when they went after the coastal guns.

“I didn’t eat,” says Adams. “Just drank some coffee along the way. Our boys were out of ammo when we got to them and they had been fighting the German with guns and knives. And don’t ask me what I said when I got to the first Ranger. All I remember is that he got out of his hole and shook hands with me and was damn glad to see me. There wasn’t many of them left.”

Landing on the left of the Rangers on Omaha was the 116th Infantry of the 29th Division. T/Sgt. Granville Armentrout, who used to be a plumber in Harrisburg, Pa., came in with the 1st Battalion over a beach “that had more dead men on it than live ones.”

Armentrout has been around the Army awhile; he talks and thinks like the infantry platoon sergeant he was on D-Day. The first thing he tried to do was get his men dispersed because they were all bunching up behind the seawall. Then he chewed some of them out because they had dropped the Bangalore’s that he needed to blow the seawall on the beach. He went back to get the Bangalore’s and figured that his number would come up when he used them. But his lieutenant, a new man who had come in from the Air Force for some reasons, took the Bangalore’s away from him and blew the wall. “He sure had guts,” Armentrout says. “And some kraut put 10 bullet holes in those good guts of his a little later.”

Armentrout believes that the 29th men froze on the beach momentarily because casualties had broken down the chain of command and not because they were afraid to move. It was a day where the brass had to show the stuff they were made of, and Armentrout remembers “Col. Canham and Gen. Coda walking up calmly and giving us the push we needed.”

“And I’ll never forget Col. Canham,” says Armentrout. “He had his two wounds tied up with several handkerchiefs and was waving his pistol around like it was a 105 howitzer.”

They went up the steep hills towards their objective of Vierville Sur Mer, and Armentrout noticed that his old men kept moving and shooting while some of the replacements let themselves become sitting ducks. When he stumbled over his first German in a shell crater he beat him viciously with his rifle butt before he realized the German was already dead. On top of the hill where they reorganized the platoon they saw other Germans lying motionless in the open ground they had to cross. When they began their advance the apparently dead Germans came to life and pumped burp guns at them.

“And that was the way it went,” Armentrout relates. “I lost some of my old men on the beach and more going across the field. Every time a boy went down who had been in the platoon a long time, he would call for me. Usually I couldn’t stop. Before St. Lo they knocked out practically all the old men who were left. That’s where I blew my top. There was just something about them calling for me and me not being able to do anything about it that got me.”

On the beach to the left of the where Armentrout landed, the wounded of the 1st Division suffered too, for the high waves of the incoming tide drowned some of them before medics could make it through the machine-gun fire to get them. Tech.-5 Rafael T. Niemi of the 16th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion, a replacement, was there, and he knew enough to do what the invasion-wise NCOs and officers of the Red One told him to.

His boat driver had taken a direct hit by a German artillery shell as they were embarking and shrapnel had killed eight other men. Other boats coming in with enough troops to build up the assault wave snafued their schedule and jammed together to make perfect targets for the Boche. The waiting men dug in cautiously as best they could because a mined beach is no place to sink a careless shovel.

Finally Brig. Gen. (then Col.) George A. Taylor organized the men for the assault with his practical order that they go inland and die instead of waiting for death on the beach. “I can still hear that colonel telling us we were going up the hill,” says Niemi, who didn’t know it was Taylor. “And at first I felt like shooting him with my M1. But now I feel different about it. I wouldn’t be here if I had stayed on the beach.”

And that was D-Day as the men remember it who patrol the roads along which the troops drove towards each other to join near Carentan.

Most of the American troops and French civilians had the same split-second relationship on D-Day as occurred when Raymonde Jeanne, who works in the General store at Ste. Mere Eglise, looked out of her bedroom window the night of June 5, and saw an 82nd paratrooper in the street. She threw him a rose and, unless Raymonde is romanticizing the incident, he kissed it and walked out of her life with the rose in one hand and his grease gun in the other.

The French remember. In Ste. Mere Eglise, as in every village, the families go to the American cemeteries and place flowers on the grave of their “adopted” son each Sunday. Often they write to the wife or mother and enclose a picture of the grave as it looks with the flowers.

Gone, of course, is the pre-invasion conception of the Normans that our coming would be a costless thing that would not disturb the economics of life on the rich farms along the coasts.

The peasants and townspeople paid for their liberation in lives, in wrecked homes and depleted dairy herds. Some grumble about these things, but the majority think the bigger sacrifice was made down on the beaches. And the same majority seem to understand why most GIs, unlike Raymonde’s gallant trooper, were very rough with them on D-Day.

“All evening on June 5,” says Monsieur Remand, the mayor of Ste. Mere Eglise, “we watched in the trees, on the houses, and on the church.” And all night the four machine guns that the Germans had in the church steeple keep shooting. But we are happy, because the Americans have come and we want to help them so much.

“But in the morning when I go out and find the captain of the paratroopers and speak our welcome to him in English, he refuses to shake my hand. I felt very bad. Now we understand that the Americans at first could not trust anyone. But the people felt very bad”.

Mademoiselle Andrée Manoury of Carentan wanted to help the Americans too and she secretly took exactly 72 lessons in English before one of the American bombs that blew up the German gas dump also wrecked her home and forced the family to take to the fields. But while Andree wasn’t there to welcome the Americans when they came, one of the town’s richest citizens was, and his wine flowed free.

Now the positions of Andrée and the rich citizen are somewhat different. She is the interpreter for the MPs in Carentan and he is in jail charged with making too much money from the Germans.

Not all of the problems of liberation, including collaborators, have been solved in Normandy. Those peasants who during the occupation sold butter and eggs to the German black market are selling them now to French racketeers. On another score the traditional Catholicism of agrarian Normandy expresses itself in some talk about the Russian displaced persons who are lusty rather than genteel and who seldom go to mass. And the good food fed to both Russian displaced persons and German prisoners causes some comment among persons with anti-American axes to grind.

The mark of the Boche, in the opinion of Mademoiselle Barbier, the schoolteacher that the paratroopers go back to visit, isn’t something that can be wiped out of Normandy in a day or a year.

“We no longer use the books that we had when the Germans were here,” she says. “And now we can sing the Marseillaise and Chant du Départ, and I have taught my children America. But the older children who learned to sing when the Germans were here, still sing in that awful way the Germans do. It will be some time yet before they sing like the French again.”

For the Normans who were poor, the liberation has brought economic benefits along with liberty. Madame Furor who lives in Colleville with her blind husband and her daughter Bernardine will tell you proudly that she has gained many pounds since the 1st Division ran the Germans out. And while few 1st Division men know it, the Furor family was as much in D-Day as they were. The Furors lived in the house across the little red brick chateau with the Norman towers on the road that leads up from the beach to Colleville. When the naval bombardment started they watched it until all the windows in the house shattered and then went to the trench they had dug in the front yard.

When the Germans withdrew from their positions around the road the family kept to the trench which was now in the target area of enemy artillery. Several times Americans saw them and discussed shooting them for snipers and Bernardine recalls, “Oh, I am frightened.”

Eventually some doughboy came along who offered Bernardine chocolate, but she was as suspicious of them as they were of her because Germans had told her that the Americans considered all French on the coast to be traitors and would offer her poisoned candy. It wasn’t until D plus-1 that she decided to eat some, and her admiration of Yanks dates from the first bite.

There isn’t even an MP in Colleville now but Bernardine, who doesn’t speak English very well, remembers the days when the road up from the beach was alive with troops coming in to help finish what the D-Day boys began.

And standing by the beach Bernardine will look up to the hill that once seemed so high to the boys of the Red One, clasp her hands to her breast without at all looking like a bad actress and say:

“Up here go many Americans. Many! All ride trucks that make dust and all say to me, ‘Haylo, baybee. Comment allez-vous?’ It is sad they no come back.”

(AP files a News Report on the Internet, June 19, 2018)

In this undated photo, provided by family member, Susan Lawrence on Wednesday June 13, 2018, twin brothers Julius Pieper, left, and Ludwig Pieper in their U.S. Navy Uniforms. For decades, he had a number for a name, Unknown X-9352, at a World War II American cemetery in Belgium where he was interred. On Tuesday, June 19, 2018 Julius Pieper will be reunited with his twin brother in Normandy, where the two Navy men died together when their ship shattered on an underwater mine while trying to reach the blood-soaked D-Day beaches. (Susan Lawrence via AP)

June 19, 2018 3:53 PM EST

COLLEVILLE-SUR-MER, France (AP) — For decades, he was known only as Unknown X-9352 at a World War II American cemetery in Belgium where he was interred.

On Tuesday, Julius Heinrich Otto "Henry" Pieper, his identity recovered, was laid to rest beside his twin brother in Normandy, 74 years after the two Navy men died together when their ship shattered while trying to reach the blood-soaked D-Day beaches.

Six Navy officers in crisp white uniforms carried the flag-draped metal coffin bearing the remains of Julius to its final resting place, at the side of Ludwig Julius Wilhelm "Louie" Pieper at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial.

The two 19-year-olds from Esmond, South Dakota, died together on June 19, 1944, when their huge flat-bottom ship hit an underwater mine as it tried to approach Utah Beach, 13 days after the D-Day landings.

While Louie's body was soon found, identified and laid to rest, his brother's remains were only recovered in 1961 by French salvage divers and not identified until 2017.

A lone bugler played taps as the casket was lowered in an end-of-day military ceremony attended by a half-dozen family members, closing a circle of loss. Each laid a red rose on the casket and two scattered American soil over it.

The Pieper twins, both radiomen second class, are the 45th pair of brothers at the cemetery, three of them memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the cemetery. But the Pipers are the only set of twins among the more than 9,380 graves, according to the American Battle Monuments Commission.

The cemetery, an immaculate field of crosses and Stars of David, overlooks the English Channel and Omaha Beach, the bloodiest of the Normandy landing beaches of Operation Overlord, the first step in breaching Hitler's stranglehold on France and Europe.

"They are finally together again, side by side, where they should be," said their niece, Susan Lawrence, 56, of Sacramento, California.

"They were always together. They were the best of friends," Lawrence said. "Mom told me a story one time when one of the twins had gotten hurt on the job and the other twin had gotten hurt on the job, same day and almost the same time."

The story of how the twins died and were being reunited reflects the daily courage of troops on a mission to save the world from the Nazis and the tenacity of today's military to ensure that no soldier goes unaccounted for.

The Pieper twins, born of German immigrant parents, worked together for Burlington Railroad and enlisted together in the Navy. Both were radio operators and both were on the same unwieldy flat-bottom boat, Landing Ship Tank Number 523 (LST-523), making the Channel crossing from Falmouth, England, to Utah Beach 13 days after the June 6 D-Day landings.

The LST-523 mission was to deliver supplies at the Normandy beachhead and remove the wounded. It never got there.

The vessel struck an underwater mine and sank off the coast. Of the 145 Navy crew members, 117 were found perished. Survivors' accounts speak of a major storm on the Channel with pitched waves that tossed the boat mercilessly before the explosion that shattered the vessel.

Louie's body was laid to rest in what now is the Normandy American Cemetery. But the remains of Julius were only recovered in 1961 by French divers who found them in the vessel's radio room. He was interred as an "Unknown" at the Ardennes American Cemetery in Neuville, Belgium, also devoted to the fallen of World War II, in the region that saw the bloody Battle of the Bulge.

Julius' remains might have stayed among those of 13 other troops from the doomed LST-523 still resting unidentified at the Ardennes cemetery. But in 2017, a U.S. agency that tracks missing combatants using witness accounts and DNA testing identified him.

Lawrence, the niece, said the brothers had successfully made the trip across the English Channel on D-Day itself, and "they had written my grandparents a letter saying, do not worry about us we are together."

"My grandparents received that letter after they got word that they (their sons) had passed away," she said.

The Pieper family asked that Louie's grave in Normandy be relocated to make room for his twin brother at his side.

The last time the United States buried a soldier who fought in World War II was in 2005, at the Ardennes American Cemetery, according to the American Battle Monuments Commission.

By MARK D. CARLSON and VIRGINIA MAYO

From Associated Press

June 19, 2018 3:53 PM EST

Elaine Ganley in Paris also contributed to this report.

(Copyright 2018 by the Associated Press.)

All rights reserved.

(News Article Received via an Internet News Service on June 20, 2018)