Background: In April of 2022, I received three personal photo albums that were filled with approximately 90 Black and White images that were taken by Captain Hank Thinnes during his years of duty with the United States Army near Berlin, Germany (1938 onward). Speaking fluent German during his course of duty and was trained specifically as a “Forward Observer” for heavy artillery, and able to travel with a small format camera, taking many black and white images during his travels in and about Berlin and the country sides in general of the German landscape at that time. The print size of the images was 3 3/4” x 2 1/2” and the quality of the images ranged from excellent to very poor, with tares, folds, creases, and deterioration of the images themselves through age and storage conditions, leaving their marks and degradations on the images over these past many years.

Fortunately, he had made short notations in pencil below each image on the page that held that image, and in some case small references to the history of that time. All images were processed through Photoshop and much improvement in the image quality can also be now noted.

In respect to those who have now passed on, and to their descendants living now, the family has given me their permission to repair and improve all images without harm to the originals by re-imaging with a digital camera and “Photoshop” of the digital images that will be seen on these following pages of the website. No other usage of these images was granted to me nor anyone for their “use” other than this website.

Final review of all images used and the text associated with that image, will be reviewed by the owners prior to posting on the Website in 2023.

“When the US was accused of ‘plundering’ Berlin’s museums: a new Art Exhibition reveals a murky history”

An exhibition opening at the Cincinnati Art Museum reveals how 14 major museums found themselves caught up in a “morally dubious” tour of Germany's art treasures after the Second World War.

A highly controversial operation in which the US Army was accused of “plundering” some of Germany’s greatest treasures is to be examined in an exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum next month. Paintings, Politics and the Monuments Men: the Berlin Masterpieces in America (9 July-3 October) reveals how 14 major US museums found themselves caught up in what Cincinnati curator Peter Jonathan Bell describes as a “morally dubious” government venture after the Second World War.

In 1945, American members of the Monuments Men—the group of Allied army officers charged with the responsibility of recovering important works of art—risked a court martial by protesting against General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s decision to bring 202 Old Masters paintings from Berlin’s state museums to the US, allegedly for safekeeping. Their advice was ignored, and what became known as the “Berlin 202” pictures were shipped for storage to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

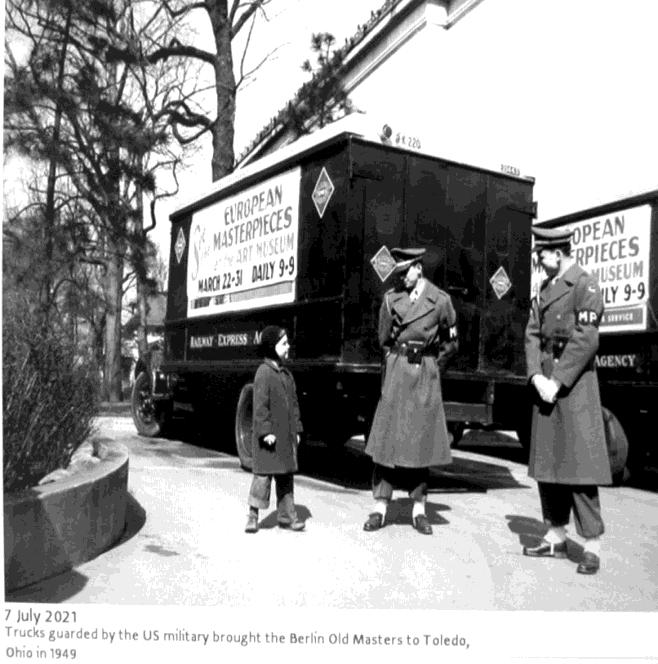

Trucks guarded by the US military brought the Berlin Old Masters to Toledo, Ohio in 1949 Courtesy of Cincinnati Art Museum.

A highly controversial operation in which the US Army was accused of “plundering” some of Germany’s greatest treasures is to be examined in an exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum next month. Paintings, Politics and the Monuments Men: the Berlin Masterpieces in America (9 July-3 October) reveals how 14 major US museums found themselves caught up in what Cincinnati curator Peter Jonathan Bell describes as a “morally dubious” government venture after the Second World War.

In 1945, American members of the Monuments Men—the group of Allied army officers charged with the responsibility of recovering important works of art—risked a court martial by protesting against General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s decision to bring 202 Old Masters paintings from Berlin’s state museums to the US, allegedly for safekeeping. Their advice was ignored, and what became known as the “Berlin 202” pictures were shipped for storage to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

The pictures were eventually returned to Germany in 1949, but first they were exhibited in DC and then sent on a tour, starting with New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and moving on to the major art museums in Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Detroit, Cleveland, Minneapolis, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, St Louis, Pittsburgh and Toledo.

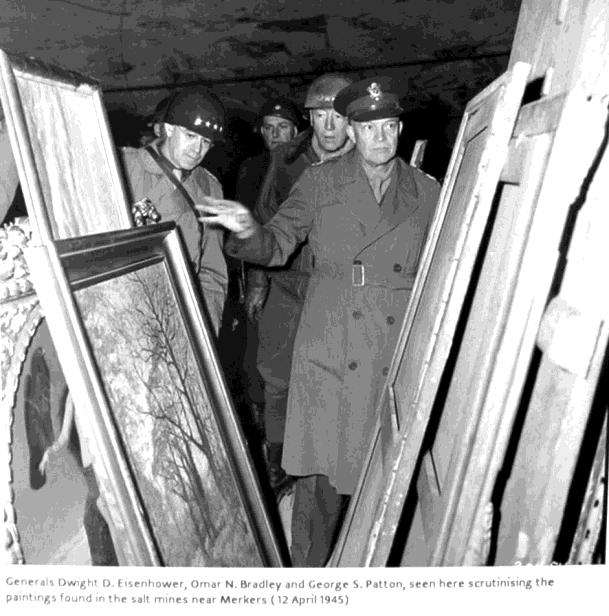

The story began in April 1945, when US soldiers discovered a treasure trove of art in the salt mines near Merkers, in central Germany, hidden by the Nazi regime to protect them from bombing raids. The Monuments Men brought them to a central collecting point in Wiesbaden (near Frankfurt) for temporary storage until they could be returned to their owners. The operation was largely successful for a huge number of works, but Berlin’s finest Old Masters had a different fate.

The US Army decided that the 202 paintings belonging to Berlin museums should be temporarily taken to America, ostensibly for safekeeping, on the grounds that “expert personnel [was] not available to assure their safety” in Germany, according to a White House statement at the time. Dating from the 16th to 19th centuries, they included paintings by Fra Angelico, Bellini, Bruegel, Caravaggio, Chardin, Cranach, Dürer, Van Eyck, Holbein, Manet, Poussin, Raphael, Rembrandt, Rubens, Tiepolo, Tintoretto, Titian, Velázquez and Vermeer, among others.

*Wiesbaden Manifesto Walter Farmer (1911-97), the head of the Wiesbaden collecting point (and a Cincinnati citizen after the war), was shocked by the military decision. He feared that this would damage the reputation of the Monuments Men and endanger the condition of the paintings, later describing it as “plunder”.

In November 1945, Farmer and his fellow Monuments Men signed a letter of protest to their superiors. Later dubbed the Wiesbaden Manifesto, their concerns were ignored within the army—although the leaked document caused concern in art circles. The paintings were sent by sea to America, reaching the storerooms of the National Gallery of Art the following month. A little more than two years later, the US Army decided to return the Berlin 202, but first the pictures were to be exhibited in a tour across American art museums. While officials at the time professed the works were only brought to the US “to protect them until they could be safely returned to their owners,” Bell says, “many would see it as a stretch to say that touring them around is keeping them safer than sitting tight in a museum building in Germany or DC”. Altogether, the exhibitions were seen by almost 2.5 million people. The paintings were eventually shipped back to Germany in groups, all arriving in Wiesbaden by May 1949.

The works’ history does not end with their return to Wiesbaden, because of Germany’s post-war divisions. The paintings later went on display in Wiesbaden’s museum, where they remained until 1956, when they were sent to a museum building in Dahlem, a western suburb of Berlin in the American zone. It was not until 1998, eight years after reunification, that the pictures finally returned to central Berlin, where most now hang in the Gemäldegalerie.

The Cincinnati Art Museum exhibition will include four of the 202 works, which the Gemäldegalerie is temporarily sending on loan: paintings by Konrad Witz (attributed), Philips Koninck, Antoine Watteau and, most importantly, Sandro Botticelli’s Ideal Portrait of a Lady(1475-80).

7 July 1949 Trucks guarded by the US Military brought Old Masters to Toledo, Ohio in 1949. |

Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley and George S. Patton, seen here reviewing the paintings in the salt mines near Markers (12 April 1945). |

National Gallery, German art museum that is part of the National Museums of Berlin. It is housed in six buildings: the Old National Gallery (and its affiliate, the Friedrichswerder Church; the Hamburger Museum; the Museum; the Collection (Sammlung Scharf- Gerstenberg); and the New National Gallery (Neue Nationalgalerie). Together the museums house a collection that spans from the late 18th to the 21st century.

The National Gallery was founded as a contemporary art museum and opened to the public in 1876 in what is now called the Old National Gallery on Museum Island (Museumsinsel). Its collection originated from an 1861 bequest from consul and banker Joachim Heinrich William Wagener. After World War II, when Berlin was divided into East and West, the National Gallery was administered by East Germany from 1949, when the museum was partially reopened after war damage had been repaired, to 1990, the date of German reunification. Meanwhile, West Berlin opened the New National Gallery in 1968 to house art from the 20th century.

The building was one of the last designed by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Following reunification, the two collections were merged in 1992 and reorganized and redistributed throughout the six locations in 1993.

There was long discussion of the desirability of establishing a national gallery in Berlin, particularly during the period of revolutionary nationalism around 1848, and it became an increasingly serious proposition from 1850, when publications appeared advocating it. From the start it was bound up with the ambitions of Prussia and the wish for Berlin to become a capital of world renown. The decision was finally taken in 1861, after the death of the banker and art patron Joachim Heinrich Wilhelm Wagener, who bequeathed his extensive collection (262 artworks) to the then Prince Regent, the future King William I, in the hope of catalysing the formation of a gallery of "more recent" art. The collection was initially known as the Wagenersche und Nationalgalerie (Wagener and National Gallery) and was housed in the buildings of the Prussian Academy of Arts.

Friedrich August Stüler began working on a design for a gallery building in 1863, based on a sketch by William I's father, King Frederick William IV of Prussia. Two years and two failed plans later, his third proposal was finally accepted. Stüler died before planning was completed and Carl Busse handled the remaining details in 1865. In 1866, by order of the king and his cabinet, the Kommission für den Bau der Nationalgalerie (Commission for the construction of the national gallery) was created. Ground was broken in 1867 under the supervision of Heinrich Strack. In 1872 the structure was completed and interior work began. The opening took place on March 22, 1876 in the presence of William I, who was by then German Emperor.

The building, today the Alte Nationalgalerie, resembles a Greco-Roman temple (a form chosen for its symbolism that, it has been pointed out, is not well suited to displaying art) and is stylistically a combination of late Classicism and early Neo-Renaissance. It was intended to express "the unity of art, nation, and history", and therefore has aspects reminiscent of a church (with an apse) and a theatre (a grand staircase leading to the entry) as well as a temple.

An equestrian statue of Frederick William IV tops the stairs, and the inside stairs have a frieze by Otto Geyer depicting German history from prehistoric times to the 19th century. The inscription over the door reads "To German art, 1871" (the year of the founding of the Empire, not the year the gallery was completed). On his first visit to Berlin, in November 1916, the young Adolf Hitler sent a postcard of this building to a comrade in arms to congratulate him on receiving the Iron Cross.

The first director of the National Gallery was Max Jordan, who was appointed in 1874, before the building was completed. When the building opened, in addition to Wagener's collection, it contained over 70 cartoons for friezes on mythological and religious subjects by Peter von Cornelius; high-ceilinged galleries were designed to accommodate them. Wagener's collection was not limited to German art; in particular, it included Belgian artists who were popular at the time; and under Jordan the gallery's holdings rapidly came to include an unusually large collection of sculpture and a drawings department. However, Jordan was hampered throughout his tenure by the Regional Art Commission, which was made up of representatives of the academic art establishment and resisted all attempts to acquire modernist art.

In 1896, he was succeeded as director by Hugo von Tschudi, formerly assistant head of the Berlin museums under Wilhelm von Bode. Although he had previously had no association with modern art, he was fired with enthusiasm for Impressionism on a visit to Paris where he was introduced to the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, and became determined to acquire a representative collection of Impressionist art for the National Gallery. When the commission vetoed his requests, he secured the patronage of a large number of wealthy bourgeois art collectors, most of them Jewish. He also rearranged the exhibition spaces, putting many items in storage to make room for works by Manet, Monet, Degas and Rodin as well as the earlier Constable and Courbet. One of the first, soon after Tschudi took up the post, was Manet's In the Conservatory; in 1897, the Berlin National Gallery became the first museum in the world to acquire a painting by Cézanne. This moved the gallery decisively away from emphasis on Prussia and the rest of the German Empire. In response to complaints from the academic connoisseurs, William II decreed in 1899 that all acquisitions for the National Gallery must have his personal authorisation; Tschudi initially complied and rehung the old works, but the imperial decree proved unenforceable, prompting the Kaiser to build public monuments to his power instead. In 1901, at the inauguration of the memorials on the Siegesallee, he gave a speech denouncing "gutter art" which became known as the Rinnsteinrede (gutter speech). Late 19th-century view of the Crown Prince's Palace, which became the National Gallery's annexe for modern art in 1919

Tschudi also had a great appreciation for the German Romantics, many of whose paintings were included in Wagener's original bequest. An exhibition of 100 years of German art at the National Gallery in 1906 contributed to reawakening interest in artists such as Caspar David Friedrich. This was also an interest shared by Tschudi's successor, Ludwig Justi, who was director from 1909 to 1933 and added to the gallery's holdings in early 19th-century German painting.

In 1919, after the abolition of the Prussian monarchy, the gallery acquired the Crown Prince's Palace (Kronprinzenpalais) and used its to display the modern art. This became known as the Neue Abteilung (New Department) or National Gallery II, and met the demand by contemporary artists for a Gallery of Living Artists. It opened with works by the Berlin Secessionists, the Impressionists and the Expressionists. This was the first state promotion of Expressionist works, which were unpopular with large numbers of the public, but the collection was, in the judgement of Justi's assistant Alfred Hentzen, superior to that of all other German galleries then collecting modern art. By far the largest share of artworks in the 1937 exhibition of 'Degenerate Art' under the Nazis were taken from this collection.

Justi was one of 27 art gallery and museum heads forced out by the Nazis in 1933 under the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, to be succeeded for a few months by Alois Schardt and then by Eberhard Hanfstaengl, who was in turn dismissed in 1937; he had refused to meet with the commission under Adolf Ziegler, president of the Reich Chamber for the Visual Arts, who were charged with purging the gallery of "degenerate" works. Some artwork from a dealer had been burnt in the furnaces of the National Gallery building in 1936, and the modern art annexe in the Crown Prince's Palace was shut down in 1937 as a "hotbed of cultural Bolshevism". The gallery was placed under the control of the Berlin State Museums and Hanfstaengl was after a while replaced by Paul Ortwin Rave, who despite being more acceptable to the Nazi regime, conscientiously guarded the artworks and as the war drew to an end, went with them to the salt mine where they were to be stored for safety's sake and was there when the Red Army arrived. He remained in charge of the gallery until 1950.

|

|

During the Third Reich, Munich was slated to get another opera house. With Clemens Krauss, who served in the joint capacity of general manager and general music director, Munich was able to develop even further despite oppression and war. Clemens Krauss supplied highlights both in his career and in the history of the National Theatre with the world premières of three works by his friend Richard Strauss, three fantastic anachronisms which nevertheless became artistic reality: Friedenstag in 1938, Verklungene Feste in 1941, and Capriccio in 1942. During an Allied bombardment in the night of October 3rd. and 4th., the National Theatre was turned into an eerie ruin. Further damage and destruction as well as the proclamation of “total war” silenced the State Opera for a while

The arduous tasks of restoring the theatre to life were assumed by General Manager Georg Hartmann and his General Music Director Georg Solti. After they had successfully introduced works by Paul Hindemith and Heinrich Sutermeister, and Werner Egk had established himself in 1948 with his Faust ballet Abraxas, Hartmann and Solti put on the first post-war Munich Opera Festival in 1950, creating on a firm foundation to pass on to their successors.

The original cornerstone was laid in 1443, but the royal residence only began to take on its final form in 1701. Architect Andreas Schlüter designed the palace facades in the Italian style. With its 1,210 rooms, the City Palace subsequently became known as the biggest Baroque building north of the Alps.

Captain Thinnes made 3 small photo albums while on duty in Germany. Some of his images are now featured below and other images will be featured in the next post up to this website.

Capt. Thinnes at Kassel, Germany |

Two German deserted 88mm Anti-Aircraft guns |

Credits:

Private images from albums of Captain Thinnes, US Army

https://www.gettyimages.com/photos/bomb-berlin

Planning for the Rhine crossing had been started even before the previous year had ended. It was not just a matter of piling up men and supplies for the crossing as a great deal of training was necessary. One of the largest programs concerned the conversion of several tank regiments to use of LVTs (Landing Vehicles, Tracked), or Buffaloes as they were known to the British. These were to be used to carry the first waves of men across and they were to be followed up by a second wave traveling in assault boats. The crossings were also to require a considerable engineer involvement. Not only had the bridging equipment necessary to cross the Rhine to be assembled ready for use, but approach roads and other transport facilities had to be made ready. In the end this was managed only by the allocation of several US Army engineer regiments to help out. Ultimately over a quarter of all supplies and equipment involved in the Rhine crossings was that of engineer units.

The Allies were talking no chances. The Allied air forces were provided with the task of completely neutralizing the rump of the Luftwaffe left after the Ardennes offensive of the previous winter. Standing patrols were established over all Luftwaffe airfields likely to become involved in the crossings, mainly to prevent the Luftwaffe seeing the vast build-up of men and material close to the crossing points. New railheads had to be established to enable 662 tanks of all kinds, 4,000 tank supporters and 32,000 vehicles of every variety to be brought up. Moreover, there were 3,500 field and medium guns to be assembled, together with a quantity of really heavy artillery that would cover the main crossings.

To add to the planners’ problems the Rhine had its own say in the matter. The area where the crossings were to be made is flat and prone to flooding, and the previous winter had been so wet that by March the flood plains were still very wet: it was ideal for Buffaloes but no so easy for the other vehicles, though it was a risk that had to be accepted.

On the night of 23 March 1945 the crossings began under a barrage from all of the artillery weapons bat had been assembled. The first troops went across in Buffaloes with numbers of DD Shermans and other special vehicles in train. Air support was so intense that Wesel itself was confidently bombed by the RAF Bomber Command when Allied troops were only a few hundred yards away. This not only cleared Wesel of the enemy but prevented the Germans from moving through Wesel to counter-attack.

The Allies did not have it all their own way. The mud was so bad in places that not even the Buffaloes could make much forward progress, with the result that some of the second assault waves, crossing in boats, came under intense fire and took heavy casualties.

Opposition to the landings was patchy In places the defenders fought fiercely and in others the preliminary bombardment had been so fierce that organized defense was slight. The sheer weight of the onslaught was such that in places the Allies were soon able to wade ashore and establish sizable bridgeheads, but the main strength of the attack was yet to come.

This arrived at about midday when the first of the Allied airborne forces came into sight. What became known as the ‘armada of the air’ flew over the Rhine to disgorge two divisions of parachute troops who seemed at times to make the sky dark with their numbers They were soon followed by glider tugs that unleashed their charges to land in an area known as the Mehr-Hamminkeln.

These glider troops did not land unscathed. Despite all efforts of the Allied air forces to neutralize flak sites near the landing points, some guns escaped to concentrate their fire power on the gliders, and about one quarter of all the glider pilots became casualties in this operation. The numbers that did land safely were such that the airborne forces and the troops that had made the river crossing were able to join up, often well in advance of the anticipated times. By nightfall the Rhine bridgeheads were secure and despite some localized German counter-attacks they were across the river to stay.

It had always been realized that the crossing of the Rhine in the northern sector would be most strongly resisted, not only because of the close vicinity of the Ruhr industries but also because the gap between the Ruhr land the Dutch boarder led directly to the north German plain and the main route to Berlin.

As a result, attempts to cross by the American armies along the more southern stretches of the Rhine, although mounted be fewer men with smaller resources, were just as successful. One had occurred the day before Twenty-first Army group launched the main crossing - south of Mainz between Nierstein and Oppenheim by an assault regiment of the US 5th Division, part of XXII Corps of the Third Army, under command, needless to say, of General Patton.

The divisional commander, Major-General Leroy Irwin, made some small protest about the shortness of time he was given for the preparation, but in the face of Patton’s urgency he sent the first wave of assault boats across the 1,000-feet wide river, just before midnight, under a brilliant moon and the artillery support of a group which later complained that it could find little in the way of worthwhile targets. The first Americans to land captured seven German soldiers who promptly volunteered to paddle their assault boat black for them, and although later waves ran into sporadic machine-gun fire, the regiment was across before midnight and moving towards the east-bank villages, with support regiments flooding across behind them. By the evening of 23 March the entire 5th Division was across the river, a bridgehead formed and awaiting the arrival of an armored division already on the west bank.

During the next few days, crossings were made at Boppard and St. Goar, Worms and Mainz, and by the end of the month, Darmstadt and Wiesbaden were in US hands and armored columns were driving for Frankfurt-am-Main and Aschaffenburg beyond; further south, the French had put an Algerian division across near Germersheim. Now a huge Allied bridgehead could be formed from Bonn down to Mannheim, from which would be launched the last Western offensive designed to meet the Russians on the Elbe and split Germany in two. The main objective for the US Twelfth Army Group would be the industrial region of Leipzig and Dresden.

To the north, Montgomery’s twenty-first Army group were to drive north towards Hamburg, its left flank (the Canadians) clearing Holland of the enemy and then driving along the coast through Emden and Wilhelmshaven, its right flank (US Ninth Army) curving around the Ruhr to meet Hodges’ First Army formations at Lippstadt, thus encircling Field Marshall Model’s Army Group B in the Ruhr. After Hamburg, the British would close up to the Elbe down as far as Magdeburg, and send other forces up into Schleswig-Holstein and the Baltic.

There was some argument as to the desirability of the Twenty-first Army Group racing for Berlin, but Eisenhower, solidly supported by Roosevelt, felt that the German capital was in easier reach of the Russians who – Roosevelt was sure – would prove both co-operative and amenable in regard to post-war European responsibilities.

Stalin would doubtless have been amused had he learned of the arguments

On 1 April, Marshalls Zhukov and Koniev had arrived in Moscow for a briefing on the subject of the Battle for Berlin. Stalin informed them that the devious and conniving Western Allies were planning a swift Berlin operation with the sole object of capturing the city before the Red Army could arrive – an announcement which, not surprising in view of the recent achievements of the Red Army, incensed them both.

They had expected to mount the attack on Berlin in early May, but in these special circumstances they would accelerate all preparations and be ready to move well before the Anglo-Americans could get themselves solidly inside German territory. Which of the two fronts – Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian or Koniev’s 1st Ukrainian – should have the task, and the honor of driving straight for Berlin? – a question to which the wily Georgian left an ambiguous answer, by drawing on their planning map a demarcation line between their commands, which ended short of Berlin at Lubben, 20 miles to the south east.

It had always been realized that the crossing of the Rhine in the northern sector would be most strongly resisted, not only because of the close vicinity of the Ruhr industries but also because the gap between the Ruhr land the Dutch boarder led directly to the north German plain and the main route to Berlin.

As a result, attempts to cross by the American armies along the more southern stretches of the Rhine, although mounted be fewer men with smaller resources, were just as successful. One had occurred the day before Twenty-first Army group launched the main crossing - south of Mainz between Nierstein and Oppenheim by an assault regiment of the US 5th Division, part of XXII Corps of the Third Army, under command, needless to say, of General Patton.

The divisional commander, Major-General Leroy Irwin, made some small protest about the shortness of time he was given for the preparation, but in the face of Patton’s urgency he sent the first wave of assault boats across the 1,000-feet wide river, just before midnight, under a brilliant moon and the artillery support of a group which later complained that it could find little in the way of worthwhile targets. The first Americans to land captured seven German soldiers who promptly volunteered to paddle their assault boat black for them, and although later waves ran into sporadic machine-gun fire, the regiment was across before midnight and moving towards the east-bank villages, with support regiments flooding across behind them. By the evening of 23 March the entire 5th Division was across the river, a bridgehead formed and awaiting the arrival of an armored division already on the west bank.

During the next few days, crossings were made at Boppard and St. Goar, Worms and Mainz, and by the end of the month, Darmstadt and Wiesbaden were in US hands and armored columns were driving for Frankfurt-am-Main and Aschaffenburg beyond; further south, the French had put an Algerian division across near Germersheim. Now a huge Allied bridgehead could be formed from Bonn down to Mannheim, from which would be launched the last Western offensive designed to meet the Russians on the Elbe and split Germany in two. The main objective for the US Twelfth Army Group would be the industrial region of Leipzig and Dresden.

To the north, Montgomery’s twenty-first Army group were to drive north towards Hamburg, its left flank (the Canadians) clearing Holland of the enemy and then driving along the coast through Emden and Wilhelmshaven, its right flank (US Ninth Army) curving around the Ruhr to meet Hodges’ First Army formations at Lippstadt, thus encircling Field Marshall Model’s Army Group B in the Ruhr. After Hamburg, the British would close up to the Elbe down as far as Magdeburg, and send other forces up into Schleswig-Holstein and the Baltic.

On 1 April, Marshalls Zhukov and Koniev had arrived in Moscow for a briefing on the subject of the Battle for Berlin. Stalin informed them that the devious and conniving Western Allies were planning a swift Berlin operation with the sole object of capturing the city before the Red Army could arrive – an announcement which, not surprising in view of the recent achievements of the Red Army, incensed them both.

They had expected to mount the attack on Berlin in early May, but in these special circumstances they would accelerate all preparations and be ready to move well before the Anglo-Americans could get themselves solidly inside German territory. Which of the two fronts – Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian or Koniev’s 1st Ukrainian – should have the task, and the honor of driving straight for Berlin? – a question to which the wily Georgian left an ambiguous answer, by drawing on their planning map a demarcation line between their commands, which ended short of Berlin at Lubben, 20 miles to the south east.

When the last offensive of the Red Army was launched its aims were to advance to the Elbe and to annihilate all German resistance before them, including the capture of Berlin and the reduction of its garrison. For this purpose, Marshals Zhukov and Koniev had some 1,640,000 men under their command, with 41,600 guns and mortars, 6,300 tanks, and the support of three air armies holding 8,4000 aircraft.

To oppose them were 7 panzer and 65 infantry divisions in some sort of order, a hundred or so independent battalions, either remnants of obliterated divisions or formed from old men, children, the sick, criminals or the simple-minded, collected together by SS teams sent out from Chancellery bunkers in which Hitler and his demented entourage were living out their last fantasies, with orders to conjure yet another army from the wreckage of the Thousand Year Reich.

Unorganized and half trained though they might be, the bulk of the German formations defending Berlin against the Red Army nevertheless fought at first with a blind ferocity and a blistering efficiency which demonstrated yet again that the epitome of high morale in combat is that of the cornered rat - which is the reason he so often escapes.

But there would be no escape for the Germans now.

At dawn on 16 April tremendous artillery and air bombardment opened all along the Oder and Neisse Rivers and out of the Soviet bridgeheads stormed the first waves of shock troops. It took Zhukov’s northern thrust two days to smash through some four miles to reach the Seelow Heights, and his southern thrust to advance eight miles – and at that point they had seen no sign of a crack in the German defenses despite the casualties on both sides. Koniev’s shock troops however, were not so strongly opposed and they advanced eight miles the first day; so on 18 April Koniev fed in two tank armies and ordered them to fight their way to the north-west. Onto the Berlin suburbs. His right-hand flank brushed Lübben, but only just.

Perhaps inspired by completion, Zhukov now drove his infantry and tank armies forward with ruthless vigor, and by 19 April both his thrusts had advanced 20 miles on a front almost 40 miles in width, destroying as they did so the bulk of the German Ninth Army, immobilized in the path of the attack by lack of fuel. On 21 April General Chuikov reported that his Eighth Guards Army, which he had brought all the way from Stalingrad, was into Berlin’s south-eastern suburbs.

Koniev, having thrown his own counter into the battle for the capital, now devoted the bulk of this endeavor due westwards towards the Elbe. By 20 April two of tank armies had reached Luckenwald – thus splitting the German Army Group Centre from Berlin and the defenses in the north – and then drove two more armies given by STAVKA up towards Potsdam where on 25 April they linked up with one of Zhukov’s guard tank armies which had come around the north of Berlin – and the city, its inhabitants and its 200,000-man garrison were surrounded. On the same day, units of Fifth Guards Army reached the Elbe at Torgau and within minutes were exchanging drinks, hats, buttons and photographs with Americans of the US First Army. The scenes of triumphant comradeship and co-operation which followed were repeated up and down the central axis of Germany, as soldiers who had fought westward from Stalingrad met those who had fought eastwards from Normandy, and during the brief period in which they were allowed to fraternize, they learned to recognize each others’ qualities. It is a tragedy that friendships made then were not allowed to continue.

On 1 May, General Chuikov, now well inside the Berlin city centre, was approached by General Krebs, the Chief of the German General Staff, with three other officers bearing white flags desirous of negotiating a surrender. With almost unbelievable effrontery, the German general opened the conversation with the remark: “Today is the First of May, a great holiday for our two nations”

Considering the outrages carried out in his country by the nationals of the man addressing him, Chuikov’s reply was a model of restraint. “We have a great holiday today. How things are with you over there, it is less easy to say!” But the first moves towards an official end to hostilities in Europe and been made.

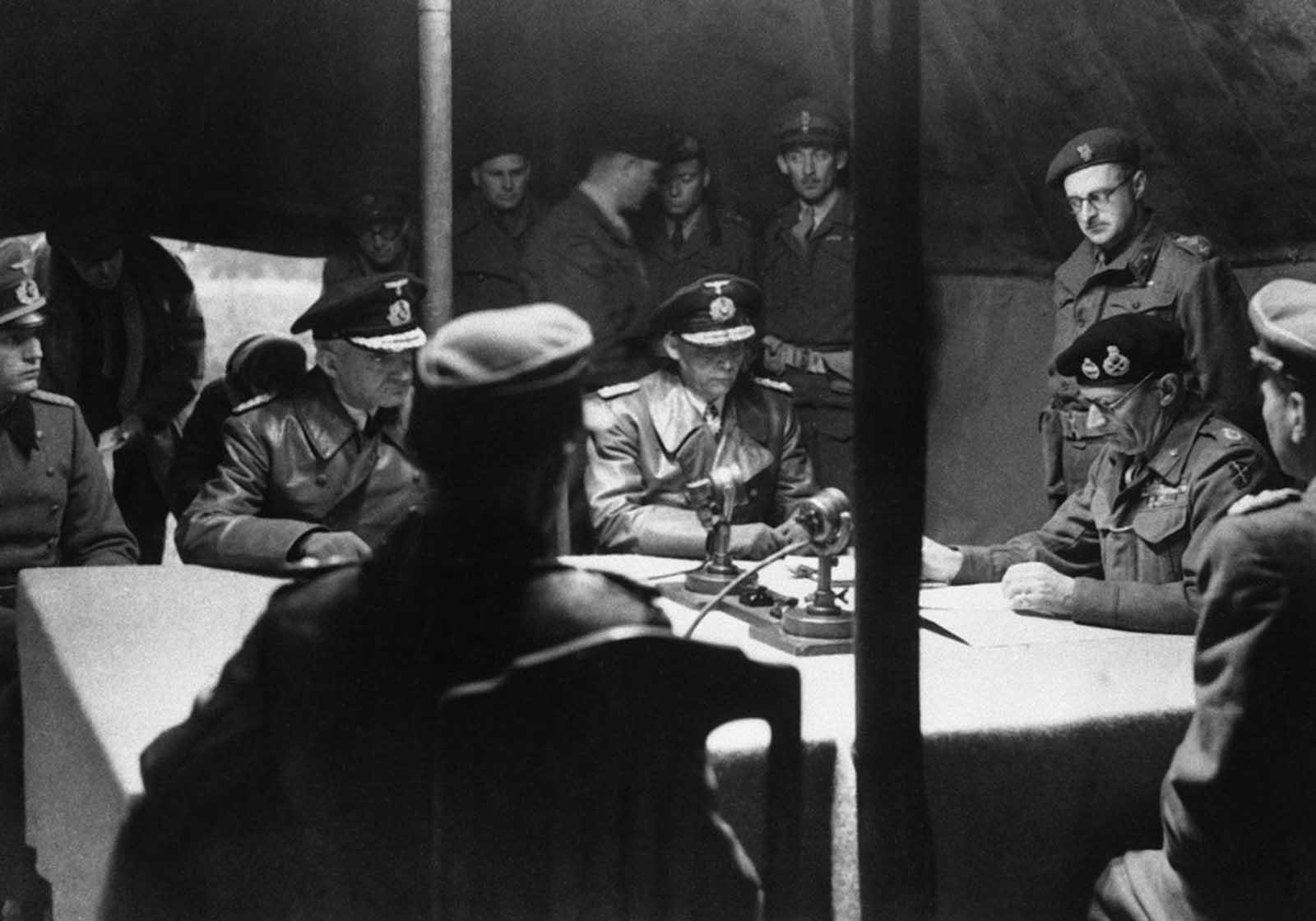

Berlin surrendered unconditionally on 2 May, on 4 May, Field marshal Montgomery took the surrender of all German forces in the north – and on 7 May the “Unconditional surrender of Germany to the Western Allies land to Russia’ was agreed, the instrument itself signed by General Jodl for the defeated, and Generals Bedell Smith and Suslaparov for the victors, General Sevez also signing for France. The war in Europe was at an end.

Hitler had committed suicide on 30 April, having first married and then poisoned his mistress Eva Braun, made a will leaving the leadership of his country to Admiral Donitz, spoken briefly to every member of his personal staff – and poisoned his dog. Afterwards, the bodies of all three were burned.

A man of enormous but demonic gifts, he had lifted his country from a position of weakness and chaos to unparalleled power, and then dropped her back into chaos again – all in the space of 12 years.

The defensive line on the Seelow Heights was the last major defensive line outside Berlin. From 19 April, the road to Berlin—90 km (56 mi) to the west—lay open. By 23 April, Berlin was fully encircled and the Battle in Berlin commenced. Within two weeks, Adolf Hitler was dead and the war in Europe was effectively over.

As result of the 1st Belorussian Front's success at the Seelow Heights and the Oder Front in general, most of the forces of the German 9th Army were encircled before they could retreat to Berlin. The city was then defended by broken formations, the Volkssturm, police, and air defense units, which resulted in the Red Army taking it in 10 days.

After the war, Zhukov's critics asserted that he should have stopped the 1st Belorussian Front's attack via the direct line to Berlin along the Autobahn and instead made use of the 1st Ukrainian Front's breakthrough over the Neisse or concentrate its armies on surrounding Berlin from the north. This would have bypassed the strong German defenses at Seelow Heights, and avoided many casualties and the delay in the Berlin advance.

Zhukov supposedly took the shortest path, the critics contend, so that his troops would be the first ones to enter the city. However, Zhukov chose the main thrust to be through the Seelow Heights not because he thought that was the quickest way to get to Berlin, but because that was the quickest way to link up with Konev's 1st Ukrainian Front and cut off the German 9th Army from the city.

Also, bypassing the Seelow Heights and attacking Berlin from the north would have exposed the northern flank of the 1st Belorussian Front to a potential attack from German forces to the north, which could have pinned Zhukov's forces against the Seelow Heights. Furthermore, in actuality only two of the five armies of the 1st Belorussian Front attacked the Seelow Heights themselves and the heights were eventually bypassed from the north as soon as there was a narrow breakthrough.

Estimates of Soviet casualties during the assault on the Seelow Heights vary from under 10,000 to over 30,000 killed.

By the beginning of 1945, the war which Germany had unleashed throughout the world had come back to consume it. In sharp contrast with what had occurred in 1918 in 1945, Germany fought, literally, to the bitter end.

The Germans held out, although by early 1945 just about everyone knew that catastrophic defeat was the inevitable outcome. They did not give up even when Russian soldiers arrived in the garden of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. Not even the Japanese resisted like that.

By March, Western Allied forces were crossing the Rhine River, capturing hundreds of thousands of troops from Germany’s Army Group B. The Red Army had meanwhile entered Austria, and both fronts quickly approached Berlin. Strategic bombing campaigns by Allied aircraft were pounding German territory, sometimes destroying entire cities in a night.

In the first several months of 1945, Germany put up a fierce defense, but rapidly lost territory, ran out of supplies, and exhausted its options. In April, Allied forces pushed through the German defensive line in Italy. East met West on the River Elbe on April 25, 1945, when Soviet and American troops met near Torgau, Germany.

On April 30th, as Russian troops entered the outskirts of Berlin, Adolf Hitler committed suicide. The leadership of Germany passed to Joseph Goebbels, but within 24 hours he too took his own life. Elsewhere, other Nazi leaders were either in Allied custody or running like fugitives.

The German surrender came on May 7th, a week after Hitler’s death. Nazism, the proud and boastful movement of the 1930’s, was drawing its final breaths. The Nazis had promised the German people dignity, respect, and prosperity – and for a time seemed to deliver on these promises.

But their ultimate legacy was a war that had claimed the lives of more than 48 million people, a racial genocide unlike any other in history, and a Germany that was devastated, occupied, and torn apart for more than 40 years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Britain’s Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, right, reads over the surrender pact, while senior German officers, from left, Major Friedel, Rear Admiral Wagner, and Admiral Hans-Georg Von Friedberg, look on, in a tent at Montgomery’s 21st Army Group headquarters, at Luneburg Heath, on May 4, 1945. The pact agreed a ceasefire on the British fronts in north west Germany, Denmark and Holland as from 8am on May 5. German forces in Italy had surrendered earlier, on April 29, and the remainder of the Army in Western Europe surrendered on May 7,1945 on the Eastern Front, the German surrender to the Soviets took place on May 8, 1945. More than five years of horrific warfare on European soil was officially over.