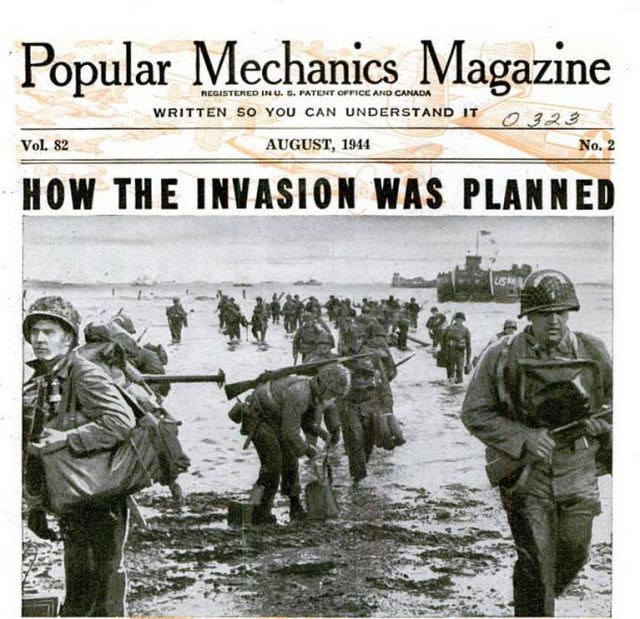

In speaking of the greatest military assault in history—the invasion of France by the Allied forces—Prime Minister Churchill said:"Everything proceeded according to plan. And what a plan it was!"

The magnitude of that plan, worked out by persons Herr Hitler once called "military idiots," stagers the imagination. It embraced the air, ground and sea forces of this nation and our allies. It hurdled problems of supply and transport, of pre-invasion training, of production and improvement of weapons, of photo-reconnaissance and mapping on a scale that makes the battle plans of Napoleon look like a game of checkers. More than 125,000,000 maps alone, just to mention one item, were used in perfecting the master invasion plan.

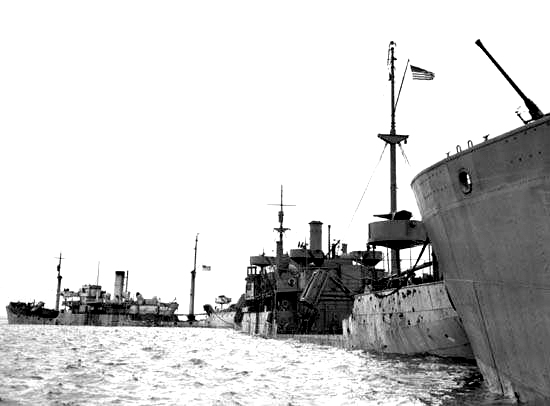

The success of that plan was demonstrated to a stunned enemy and a surprised world on D-Day. Four thousand ships carried the magnificently equipped troops across the English Channel under protection of a powerful naval force including 12 battleships, and thousands of aircraft.

Parachute and airborne divisions, spearheading the invasion, filled the sky over Normandy. As a climax to the "combined operations" attack on German coastal defenses, Allied planes dropped 11,000 tons of bombs in the eight hours preceding the landing and big naval guns pounded the coast before the troops went ashore. In 10 minutes, 600 naval guns fired 2,000 tons of shells at Nazi batteries.

Behind the invasion plan were lessons learned the hard way on the beaches of Dunkirk, Diep North Africa, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, Attu and Kwajalein.

After the general timing for the invasion was set at Teheran, the exact site for the landing was decided upon. This remained a closely guarded secret until H-Hour on D-Day. The low sandy beaches of Normandy between Le Havre and Cherbourg were selected not only for their proximity to great bases and supply depots in England, but because the region was suitable for amphibious operations and the defenses were within easy range of our aircraft.

The Norman coast, however, was just about the center of Hitler's famous West Wall. German boasts about the invulnerability of this West Wall acted as a boomerang, for they inspired the most careful reconnaissance in military history.

What happened to this West Wall on D-Day? The answer forms a revealing chapter in the invasion plan. For months our troops had been storming a replica of that West Wall set up along the coast of England.

From information obtained from Commando and Ranger raids on the French coast, from the French underground, from photo-reconnaissance, from scouting parties in small boats and midget submarines came a complete picture of German coastal defenses. The only thing missing was the secret rocket weapon which the Nazis threatened would blow England to bits.

The Nazi shore defenses consisted of a ring of tubular steel scaffolding build under water 150 yards out from the high water line, and behind this a double apron of wire fence, concrete antitank barriers in zigzag arrangement with protruding steel prongs (called "horned scullies" by our troops), and another double apron of wire fence. On the beach above the high water line was a three-foot barbed wire fence, a mine field, and intricate deep wire obstacle, an antitank ditch, concrete antitank wall, and "dragon's tee"—concrete blocks to stop tanks.

Behind this maze of beach defenses were pillboxes; farther back, heavy artillery. With the mined waters off shore—which were cleared by minesweepers during the early hours of D-Day— this composed the coastal sector of Hitler’s West Wall.

A duplicate of these defenses was built by American and Royal engineers at a pre-invasion training base. When the assault divisions of engineers and infantry arrived in the first landing barges, they knew how to blast a gap through these barriers. After the engineers had cleared a path for the assault infantry to advance on the pillboxes, the first heavy equipment to come ashore was the bulldozers.

Airborne divisions were used on a scale that dwarfed the German landings at Crete and our own in Sicily. An airborne division is made up of a regiment of paratroop infantry, two glider regiments and miscellaneous units, such as engineers, quartermaster, signal corps, medical and others. One paratroop innovation in Normandy was the dropping of dummies which confused the Germans as to where the real landings were to be made. Adding injury to insult, some of the dummies were filled with explosives.

The spearheading paratroopers, all with particular jobs to perform and special targets to attack, cleared strips for the “one-mission” gliders to land men and equipment. Some gliders carried light tanks. The glider regiments quickly build landing strips for the troop transports. The location of these airstrips was selected months in advance from aerial photos. The calculations from these photos are so accurate that the number of cubic yards of earth to be moved can be closely estimated. This careful planning was one reason five airstrips were completed a few days after D-Day. This was an important factor in the rapid advance and the joining up of airborne and seaborne infantry to consolidate positions along 60 miles of coast.

While troops were training and great piles of material were accumulating in England, our air fleets were carrying out a plan for strategic bombing of enemy targets. On their “priority” list were submarine pens, aircraft, munitions and armament plants, oil refineries, synthetic rubber factories and all industries producing goods for the Nazi machine. The Luftwaffe’s wings were pinned back in the air and on the ground, according to plan. The result was that on D-Day Allied Supreme Headquarters could estimate the Germans had a maximum of 1,750 fighters and 500 bombers to combat the 7,500 Allied planes operating with the invasion forces. The plan worked so well that the weakened Luftwaffe left the sky to the Allies on D-Day.

The air attack wound up with a 50-day assault on enemy transportation extending several hundred miles inland from Holland to the Bay of Biscay. Ninth Air Force fighter bombers and rocket-firing R.A.F. Typhoon fighters threw enemy transportation and communications into chaos. American Mustangs, Lightning’s and Thunderbolts added “strafe bombing” and “glide bombing” to the familiar technique of dive bombing. In strafe bombing, the fighters come in low and plant delayed-action bombs before pulling up to almost 90 degrees. In glide bombing, the angle of descent is more gradual than in dive bombing and the ascent much sharper. At 400 to 500 miles an hour, the planes are too fast to be tracked by Nazi flak batteries.

The region around Caen was marked on the master invasion plan as the focal point for pre-invasion bombing, but care had to be taken not to tip our hand in advance of D-Day. Twenty-one days before D-Day airfields and communication centers were bombed within 130 miles of Caen.

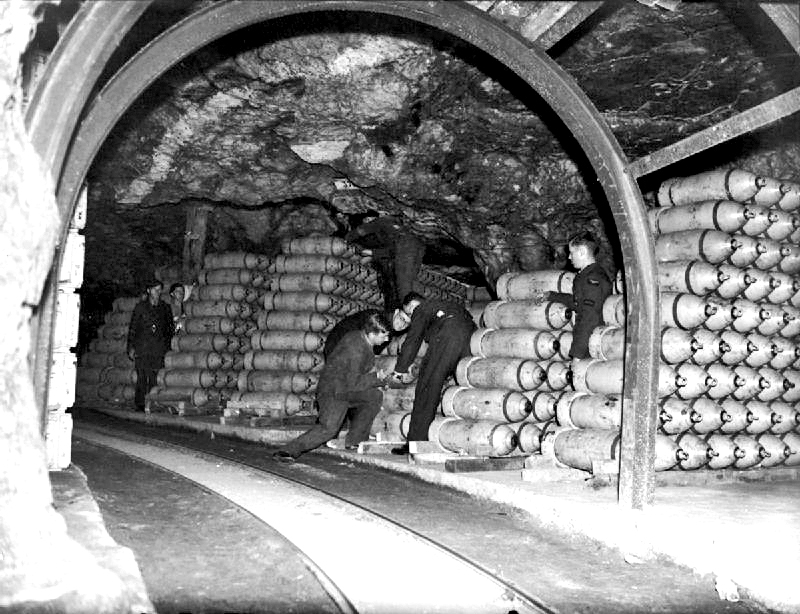

The next step was a concentrated assault on coastal batteries, set in 30 inches of concrete, along the invasion site. This attack was carried out on the eve of D-Day and repeated 30 minutes before H-Hour. Night and day fighters were used, in the final assault joined by 1,350 Flying Fortresses B-17s and Liberators B-24s. The 11,000 tons of bombs mentioned earlier, were dropped in this final phase. Image: RAF Fauld Tunnel with stacked 250 pounders. (One of many locations in the country.)

During the actual landing, fighters covered every beach operation. American Thunderbolts flew high cover, British Spitfires flew low. Night bombers laid smoke screens. Other planes protected the convoy across 70 miles of channel.

One of the greatest problems for the invasion planners was the shipping of gigantic stores of fighting equipment and supplies to England, assembling the equipment and distributing it to coastal depots. Every one of the thousands of men landed in France required about 10 ship tons of overall equipment, and an additional ship ton every 30 days. The number of separate items needed was about a million. Some of these million items had to be accumulated in millions, resulting in astronomical totals. These supplies, ranging from M-4 tanks, 240-mm howitzers and flame throwers, to bazookas, razor blades, and carrier pigeon feed, were moved by ships on a rigid timetable.

For two years these supplies flowed steadily to depots scattered over England. The Army Service units—ordnance, engineers, signal, medical, transportation, quartermaster and others—built up stock piles so large there was no chance of putting many under cover. Fields were blanketed with guns, rocket weapons, amphibious vehicles such as the famous “duck,” trucks, half tracks, bulldozers, ambulances. The only protection from enemy eyes at these open-air depots was camouflage and the fact that daytime flying was too unhealthy for the enemy over England. One Yank protested that if we didn’t stop piling up equipment, the island would surely tip.

One of the most effective new weapons in the invasion was a 50-pound rocket projectile that can be fired from ground positions, from barges, or airplanes, and can be loaded with explosives or chemicals for laying smoke.

The supply line extended back across convoy lanes, through U.S. embarkation ports, to depots in this country with 245,000,000 square feet of storage space. The process of moving supplies to England was gauged by the general timetable, radioed requisitions from supply officers in England, and the availability of ships. In one month, about 1,500,000 ship tons of cargo were shipped from New York alone.

When the convoys left U.S. ports, supply officers notified British ports of the contents, not only of the ships but of certain holds in the ships. In this way, supply officers in England earmarked items for the various depots so the goods could keep moving. Some of the high-priority cargo was moved by air as D-Day approached. Our commanding officers insisted on “amphibious packing” of goods so that they would remain intact after a dunking. Aviation gasoline and fuel for tanks and trucks by the millions of gallons were stored. About 60 percent of the deadweight tonnage moved to front lines was gasoline and oil. Fuel had to be transported in oil drums until tankers could get close enough to shore to connect with portable pipelines. These lightweight pipelines, used with great success in Tunisia, would ease the problem of oil supply for our army in Europe. They are far more difficult for the enemy to see than a tank truck, and a 100-pound bomb must strike within four feet to wreck the pipe. Even then it can be quickly repaired; a thousand feet can be laid in two hours.

While the Army was piling up supplies, transporting and training a huge invasion force, the Navy was constructing amphibious bases along the British coast. Navy and Army units practiced the loading and unloading of combat teams and equipment from dozens of types of landing craft.

All the time preparations moved ahead on a grand scale, Allied Supreme Headquarters maintained the strictest secrecy as to when and where the invasion Army would strike. There were map rooms where even generals had to show special passes.

Although the Germans could not guess the place, they probably figured they could accurately set the time of day in accordance with the tides. Here they were fooled, for our invasion planners set the time four hours before high tide. Thus, most of the enemy shore batteries that had not been knocked out by our aircraft were caught napping. This plan was carried out even though General Eisenhower had to postpone the hour of attack 24 hours awaiting favorable weather.

As D-Day neared, the troops were briefed for their exact mission and reshuffled from battalions and companies into “craft loads,” ready to move at a moment’s notice. After briefing, the invasion camps were “sealed” and the men were forbidden communication with unbriefed troops or civilians. These final security measures prevented any leaks as to the hour and place of attack after briefing thousands of men.

When H-Hour came and the Navy and air crews moved the Allied forces across the channel, it was the culmination of the most minutely planned combined operation on record. The invasion forces were composed of inter-dependent units, a weak link in any one of which would have meant disaster. In the master plan, the air forces, ground troops, airborne divisions, and naval units were welded together to form the most powerful force ever hurled against an enemy shore.

They planned it that way.

https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/a15909/how-d-day-was-plan

The Allies tried all they could to confuse the enemy on D-Day and used top secret inventions to gain the upper hand.

On the eve of battle, planes flew back and forth across the Channel to drop bundles of ‘window’, now known as chaff, to disrupt enemy radar.

Just ten bombers used the technique to make the enemy believe hundreds of ‘ghost’ aircraft were above them. The bombers then jammed German radio over Northern France to hide the 1,000 aircraft that were on their way to drop parachutists behind enemy lines.

When the beach landings happened men used rocket-propelled grappling hooks attached to ropes and ladders to climb the steep Normandy cliffs in minutes rather than hours.

They were then followed by ‘Donald Duck’ Sherman tanks, which floated and used the engine to drive through water and up onto the beaches.

The artifacts were found by a woman who was clearing out her late grandparents’ belongings and it is not known how the item made its way back from Normandy to Britain.

‘The woman vendor was having a bit of a clear out of her grandfather’s shed when she found it.’

Kevin King, of Buckinghamshire-based auctioneers Marlow’s which sold a paradummy for £900 said: “It is quite rare to come across previously unknown paradummies now”.

‘Back in the 1970s a whole batch of them were found on an airfield and some of them are in museums now.

The deception, known as ‘Operation Titanic’, did draw German troops away from the Normandy beaches.

The Rupert’s were made from hessian cloth and would have been filled with sand and straw at the time. They were featured in the famous 1962 D-Day movie The Longest Day.

Mr. King said: ‘If the paradummies were any bigger then not that many of them would have fitted in the aircrafts.

‘When an object is high up in the air it is very difficult to get a proper perspective of it from the ground, especially in darkness.’

During the war the Americans also dropped their own dummies and called them Oscars.

It was an idea stolen from the Germans, who had used the technique when it attacked the Netherlands in 1940.

Paradummies have also been used in the Vietnam war as well as the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A rare dummy parachuted into occupied Europe to bamboozle the Germans on D-Day and draw their forces from the actual invasion was been found in a garden shed.

At least 500 of the 3ft. stunt puppets were dropped along with SAS soldiers at four spots away from the Normandy beaches to take the enemy away from genuine drop zones.

Sent in the middle of the night, these canvas ‘paradummies’ – nicknamed Ruperts – were designed to burst into flames when they landed so the Germans could not find them.

But one had survived combat and had been discovered at the bottom of a British garden along with some once “top secret” maps and documents.

Rare finds: A dummy parachutist that was one of 500 dropped over France on D-Day to confuse the enemy has been found in a garden shed with a number of maps, documents and artifacts.

Six SAS soldiers were parachuted in with the dolls, with equipment playing the sounds of a loud battle to make the subterfuge even more realistic.

Although they were half the size of a human, they would have appeared lifelike to those looking up from the ground on a dark night.

The artifacts above were found by a woman who was clearing out her late grandparents' belongings and it is not known how the dummy made its way back from Normandy to Britain.

May 5, 2016 David Goran

Military deception refers to attempts to mislead enemy forces during warfare. This is usually achieved by creating or amplifying an artificial fog of war via psychological operations, information warfare, visual deception and other methods. As a form of strategic use of information (disinformation), it overlaps with psychological warfare.

To the degree that any enemy that falls for the deception will lose confidence when it is revealed, and may hesitate when confronted with the truth. The Paradummy was a device first used in World War II that, used with other paratrooper units, was meant to cause an invasion by air to exaggerate the appearance, and to appear larger than it actually was.

“One of the most unusual deception operations for D-Day involved hundreds of these dummy paratroopers, known as “Rupert’s.” Early on D-Day morning they would be dropped with several real paratroopers east of the invasion zone, in Normandy and the Pas-de-Calais. The dummies were dressed in paratrooper uniforms, complete with boots and helmets. To create the illusion of a large airborne drop, the dummies were equipped with recordings of gunfire and exploding mortar rounds.”

Paradummies were used to lure enemy troops into staged ambushes. They were called “Rupert dolls” by British Troops and “Oscars” by Americans. When some of these dolls hit the ground, they explode and the pieces flew in out every direction. During WWII, these “Paradummies” descended like real parachutists with a self-igniting explosive charges on their backs. The above plywood backboard would have held the small charges and/or large firecracker size devises that would go off during decent and mistook as muzzle fire on the ground. This remaining backpack board from WW2 shows the damage from the small charges going off and probably remains in a museum somewhere in England.

The "Rupert" paratrooper dummies dropped on D-Day were not the highly elaborate and lifelike rubber dummies shown in the film ‘The Longest Day’. The actual dummies were fabricated from sackcloth or burlap stuffed with straw or sand and were only crude representations of a human figure. They only appeared human from a distance during the descent and were equipped with an explosive charges that burned away the cloth after landing to prevent the immediate discovery of their true nature. A total of 500 dummies, accompanied by a handful SAS troopers, were dropped at four locations. The SAS played recordings of battle noise, set off smoke grenades and used their weapons to further enhance the deception. The whole operation was code-named Operation Titanic.

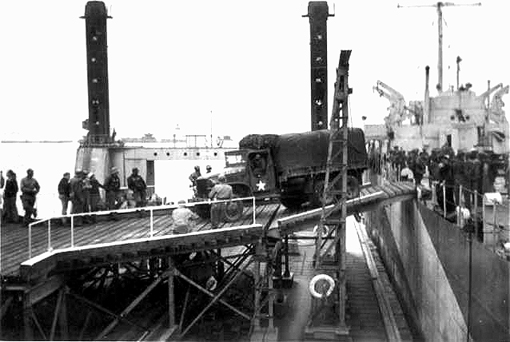

The Mulberry Harbors were built for D-Day in June 1944. The Mulberry Harbor’s purpose was to ease and speed up the unloading process of equipment and supplies so that Allied troops were continually supplied as they advanced across France after breaking out from Normandy. The success of D-Day could only be maintained if the advancing troops were kept supplied as more men continued to landed. The Mulberry Harbors was one of the greatest engineering feats of World War Two.

The Mulberry Harbor begins with the sinking of 13 old ships in a line with two entrances. The two harbors that were built are illustrated in the two mages above that calmed the ocean waters.

Support for the harbors came from on high:

Piers for the use on beaches: They must float up and down with the tide. The anchor problem must be mastered… let me have the best solution worked out. Don’t argue the matter. The difficulties will argue for themselves…- Winston Churchill. (undated)

The Mulberry Harbor was actually two artificial harbors, which were towed across the English Channel and put together off the coast of Normandy. One, known as Mulberry A, was constructed at Omaha Beach and the other, known as Mulberry B (though nicknamed ‘Port Winston’), was constructed off Arromanches at Gold Beach. Put together like a vast jigsaw puzzle, when both were fully operational, they were capable of moving 7,000 tons of vehicles and goods each day.

Each of the two artificial harbors were made up of about 6 miles of flexible steel roadways that floated on steel or concrete pontoons. The roadways were codenamed “Whales” and the pontoons “Beetles”. The “Whales” ended at giant pier heads that had ‘legs’ that rested on the seabed. The whole structure was protected from the force of the sea by scuttled ships, sunken caissons and a line of floating breakwaters. The material requirements for any part of either Mulberry A or B were huge – 144,000 tons of concrete, 85,000 tons of ballast and 105,000 tons of steel.

In its final form, the British artificial harbor had its breakwaters extended and reinforced with additions of concrete caissons (Phoenix units). Many of these came from, or were intended for Mulberry ‘A’. the American Harbor that was destroyed in the storm of June 19-22. Storms continue to be a problem, as caissons like the one above were destroyed also in September and October gales moving through the channel.

“Whales” that raised or lowered with the tide, slid on legs that sat on channel bed below. They were floated across the Channel after D Day and connected to the single roadways to the beach head that floated on pontoons.

The various parts of the Mulberry harbors were made around Britain in the greatest of secrecy. The many various parts were moved to Normandy immediately after June 6th – D-Day. By June 18th, both harbors were in use. They were meant to stay in use until the capture of Cherbourg in the north of the Cotentin Peninsula.

However, a violent storm begun on June 19th. By June 22nd, the harbor serving the Americans at Omaha had been wrecked. Parts of it were salvaged to repair the British harbor at Gold which worked for 10 months. In that time this harbor landed 2.5 million men, 500,000 vehicles and 4 million tons of goods. For all its apparent success, the idea of Mulberry did not have the support of everyone:

I think it’s the biggest waste of manpower and equipment that I have ever seen. I can unload a thousand LSTs at a time over the open beaches. Why give me something that anybody who’s ever seen the sea act upon 150-ton concrete blocks at Casablanca knows the first storm will destroy? What’s the use of building them just to have them destroyed and litter up the beaches.- (possibly Lord Mountbatten)

On 30th May 1942 Sir Winston Churchill sent to Lord Mountbatten, then Chief of Combined Operations a famous memorandum:

Churchill later wrote in 'The Second World War' Volume V:

I kept in touch with the development of this project, which was pressed forward by a Committee of specialist engineers and service representatives, summoned by Brigadier Bruce White of the War Office, Himself an eminent engineer.

Although much preparatory work and testing was done as a result of the Prime Minister's memorandum it was not until August 1943 that the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington approved the construction in the UK of artificial harbours code named Mulberry. Two harbours were planned: An American Mulberry at Omaha Beach and a British Mulberry at Arromanches.

(In late summer 1943 the actual invasion of Normandy had been planned for May 1944.)

MULBERRY HARBOR’S were a vast undertaking and one of the greatest harbor engineering feats of all times. The design, construction and erection of Mulberry Harbours was a notable military operation and a unique example of cooperation between military and civil engineers. In the second World War having been driven from the Continent we could not return except by invasion. We did not control any ports on the European mainland and could not plan on capturing any intact. Unless the invasion force was to be supplied over open beaches it was essential to provide sheltered water during all states of weather and tide to enable men, weapons, ammunition and stores to be continuously unloaded on to the beaches. There was only one solution – to build in secret artificial harbours which could be towed across the channel.

The overall organization, planning, design and especially the coordination of military and civil engineers was led by Brigadier (later Sir Bruce) White, the Director of Ports and Inland Water Transport, a Royal Engineer Officer in both World Wars and in private life a civil engineer. Whilst prototypes had been made and tested, the mass construction of the caissons did not start until December 1943 so that there were less than six months to complete the basic requirements for the landings.

Construction was undertaken at many different sites in the United Kingdom: at one time 45,000 men were employed on these tasks. The components had to be towed in advance of D-Day to assembly areas on the south coast and on D-Day (6th. June, 1944) and towed over 100 miles, in storm lashed seas to their destination, the Normandy beaches, at the same time as the assault troops. There they were assembled into the largest artificial harbor ever constructed in peace or war. The artificial Harbors sailed towards their destination on the afternoon of D-Day under the command of Rear-Admiral (later Sir William) Tennant who held the title of Rear Admiral Mulberry/Pluto and was responsible for the Cross Channel towing operation and general supervision of the two ports.

No Allied amphibious invasion in World War II left such a bitter legacy as Operation Jubilee, the ill-fated British-Canadian raid on the northern French port of Dieppe on Wednesday, August 19, 1942.

Despite partial successes to the west and the east, the main assault on the shingled beaches by 5,000 men of General Pip Roberts’s Canadian 2nd Infantry Division, 1,000 British Commandos met resistance far more fierce than expected. Many of the Canadians in the landing craft were casualties before they reached shore, and the troops and Churchill tanks that did land were pinned down by heavy German fire and blocked by obstacles. They never reached the town itself.

Almost none of the enemy installations marked for destruction was reached, and only a portion of the landing force—which included a handful of Free French soldiers and U.S. Rangers could be evacuated. Many Allied prisoners were taken. The losses were heavy: 3,600 men dead or captured and 30 tanks, 33 landing craft, a Royal Navy destroyer, and 106 aircraft destroyed. The “reconnaissance in force”—devised to provide battle experience for the untried Canadian troops and to learn about German port defense methods—was classified a disaster that tarnished the reputation of its architect, the handsome, dashing Lord Louis Mountbatten, chief of Combined Operations.

Yet “Operation Jubilee” provided important lessons for Allied planners about the difficulty of capturing a defended port and the necessity for a preliminary bombardment and adequate equipment for beach landings. Whether the lessons were worth the price paid for them has been debated ever since.

The first and most important lesson drawn from the Dieppe assault was that the Allies could not be confident of seizing a usable port in the early stages of a future and inevitable invasion on the European continent. Although the British Army had long experience in expeditionary warfare, it was generally believed that a port was needed to disembark forces.

The Germans, with little experience in amphibious tactics, remained convinced that any Allied invasion armada would be directed on a port so that its facilities could be brought into early use. Thus, German thinking remained focused on defending harbors and, should their capture seem likely, destroying such facilities in order to deny them to invaders. Even long after Dieppe, the Germans concluded that the Allies, when they came, would land near a port and then envelop it.

Returning from Dieppe on that fateful August 19, Royal Navy Commodore John Hughes-Hallett, a member of Mountbatten’s staff, was heard to comment, “Well, if we can’t capture a port, we will have to take one with us.”

Soon, stimulus was given to an ingenious strategic concept that would increasingly concern the Allied planners working on a second front. It was the concept of an artificial harbor, an intriguing idea but not a new one. As early as 1917, First Sea Lord Winston Churchill had considered the possibility of a prefabricated harbor for seizing the German Frisian Islands. Guy Maunsell, an engineer, showed Hughes-Hallett plans for an artificial breakwater as early as 1940; Tipperary-born Professor John D. Bernal, known as “The Sage” at Cambridge University, devised a plan for a floating harbor; and in December 1941, the staffers at Mountbatten’s Combined Operations headquarters were studying a scheme for creating sheltered water.

Three months before the debacle at Dieppe, the fertile-minded Churchill, now the British prime minister, resurrected his 1917 plan in a secret May 30, 1942, paper entitled, “Piers for Use on Beaches.” He wrote, “They must float up and down with the tide. The anchor problem must be answered…. Let me have the best solution worked out. Don’t argue the matter. The difficulties will argue for themselves.”

Thus, from the carnage of Dieppe would be developed the concept of two “Mulberry harbors” which would play a crucial role in Operation Overlord, the great Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander who would lead the British, American, and Canadian Armies on the European continent, recalled, “The first time I heard this idea [Mulberry] tentatively advanced was by Admiral Mountbatten in the spring of 1942. At a conference attended by a number of service chiefs, he remarked, ‘If ports are not available, we may have to construct them in pieces and tow them in.’ Hoots and jeers greeted his suggestion, but two years later it was to become reality.” The code-name, Mulberry, was chosen because it would not reveal the character or purpose of the secret project.

The concept was discussed in detail by Lt. Gen. Frederick E. Morgan, Eisenhower’s able top planner, and his COSSAC (chief of staff to the supreme Allied commander) team, and it was agreed that the invasion would require the facilities of a harbor the size of Dover, Kent. COSSAC envisioned an assault on lightly held beaches “bringing a couple of artificial harbors with us.” An important factor considered by the planners was the critical Allied shortage of landing craft. The building of the Mulberry harbors presented an enormous challenge to the British midway through the war. “The whole project involved the construction in Britain of great masses of special equipment, amounting in aggregate to over a million tons of steel and concrete,” said Prime Minister Churchill during the early stages. “This work, undertaken with the highest priority, would impinge heavily on our already hard-pressed engineering and ship-repairing industries. All this equipment would have to be transported by sea to the scene of action, and there erected with the utmost expedition in the face of enemy attack and the vagaries of the weather.” High winds and ferocious gales can whip up in a few hours in the English Channel, and the spring tides there have a play of 30 feet.

“The whole project was majestic,” said Churchill. “On the beaches themselves would be the great piers with their seaward ends afloat and sheltered. At these piers, coasters and landing craft would be able to discharge at all conditions of the tide. To protect them against the wanton winds and waves, breakwaters would be spread in a great arc to seaward, enclosing a large area of sheltered water. Thus sheltered, deep-draught ships could lie at anchor and discharge, and all types of landing craft could ply freely to and from the beaches. These break-waters would be composed of sunken concrete caissons known as ‘Phoenixes’ and blockships known as “Gooseberries”. In this painting by artist Stephen Bone, the Mulberry harbor at Arromanches, France,is the scene of a flurry of activity.

But there was much skepticism for the Mulberry harbors, particularly from the Americans on the Operation Overlord planning staff, and it was not until a Combined Operations conference, code-named Rattle, at Largs in central Scotland early in 1943 that acceptance first came for the ambitious concept. There, Commodore Hughes-Hallett and Royal Navy Captain Tom Hussey provided the necessary “ray of hope” as they argued the case and outlined the whole scheme. Many bright ideas were studied in wrestling with the problem of beating the English Channel and the German defenders of northern France at the same time. One of the most original suggestions was to create an artificial breakwater from a wall of bubbles released from the seabed, but this was abandoned as being far too risky.

The final plan called for a breakwater created by sunken blockships and the construction of an outer sea wall comprising huge concrete boxes—Phoenixes—some the size of three-story buildings. There would also be floating roadways, called Whales, made of articulated steel sections capable of moving with the 23-foot Normandy tide. At the end of each roadway would be a pier known as a Spud. In addition to the two Mulberry harbors, even more blockships were to be used to create five Gooseberries, which were sheltered anchorages for landing craft, one off each of the five assault beaches. Among the planners, according to Churchill, “imagination, contrivance, and experiment had been ceaseless,” and by August 1943 a complete design had been drawn up for two full-scale temporary harbors that could be towed across the Channel from southern England to France and put into use within a few days of the initial Overlord landings. The project was demonstrated that month for the British Chiefs of Staff as they and Churchill crossed the Atlantic Ocean aboard the liner Queen Mary for the Quebec summit conference in September 1943.

Senior officers crowded into one of the vessel’s luxurious bathrooms for a simple demonstration by Professor Bernal and one of Lord Mountbatten’s scientific advisers. Standing on a toilet seat, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord, invited his colleagues to imagine the shallow end of the bath as a beachhead. With the assistance of Navy Lt. Cmdr. D.A. Grant, Professor Bernal then floated a fleet of 20 little ships made from newspaper. Grant used a back brush to make waves, and the paper fleet sank.

Then, a Mae West lifebelt was inflated and placed in the bath to represent a harbor. The paper fleet was placed inside it. Once again, Commander Grant applied his brush vigorously to create waves, but they failed to sink the paper ships. The experiment convinced the officers of the importance of sheltered water and Mulberry harbors.

The proposal was outlined in Quebec before Churchill, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The British pressed the idea, and the Joint Chiefs eventually agreed to the construction of two such harbors—“Mulberry A” for the American landing forces and “Mulberry B” for the British and Canadians. The latter harbor was nicknamed “Port Winston.” In a memorandum, the Joint Chiefs wrote, “This project is so vital that it might be described as the crux of the whole [Normandy invasion] operation. It must not fail.”

The specifications were formidable. By D-Day plus 21 days, the two harbors were to be capable of shifting 12,000 tons of cargo and 2,500 vehicles a day. They would have to cope with the full 26-foot draft of Liberty ships and provide a shelter for landing craft in foul weather. Furthermore, each harbor had to have a minimum life of 90 days in order to funnel ashore as much manpower and material as possible before the Allied armies could secure a port. The artificial harbors were to be ready by May 1, 1944. The mammoth undertaking was to be completed in a mere eight months.

The Gooseberries were the brainchild of Rear Admiral William Tennant, who from January 1943 onward was in command of the planning, preparation, towing, and placement of the Mulberry harbors. He had a stormy relationship with the Admiralty, which was reluctant to release any usable ships to be sunk as blockships to protect the artificial harbors. Tennant determined that he needed 60 old merchant vessels and warships. At one stage, his deputy said of their lordships at the Admiralty, “We came here to get a Gooseberry, and all we seem to have got is a raspberry!” Admiral Tennant eventually got his 60 blockships. Among them were the 1911 French battleship Courbet and a Dutch cruiser. Assembled in Scotland and loaded with explosive charges, the blockships were to be sunk off the Normandy beaches.

Building the Mulberries strained the administrative capabilities of the senior British Army officer, Maj. Gen. Sir Harold Wernher, who reported, “Perhaps the greatest difficulty in getting the project underway after the plan was approved, was the vast number of interested parties who had to be consulted or thought they ought to be consulted.” A team was assembled comprising “three of the best brains from the consultant engineers in Britain, and alongside them were placed leading contractors in naval installation together with British and American officers.” At first, the team was in almost continuous session trying to solve the critical problem of designing the outer breakwater.

In the wake of the savage storm that struck the Mulberries, small craft, vehicles, and components of the harborsthemselves lie in shambles. One Mulberry was rendered completely useless by the violent weather.

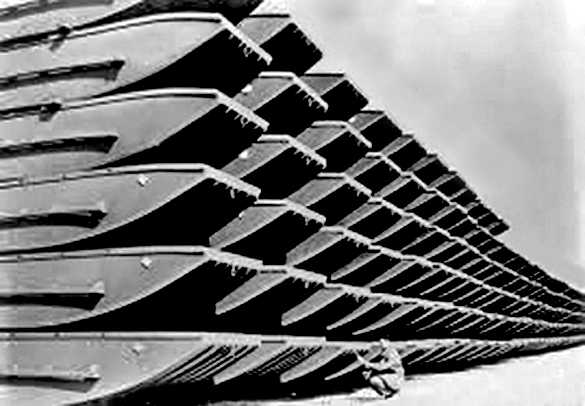

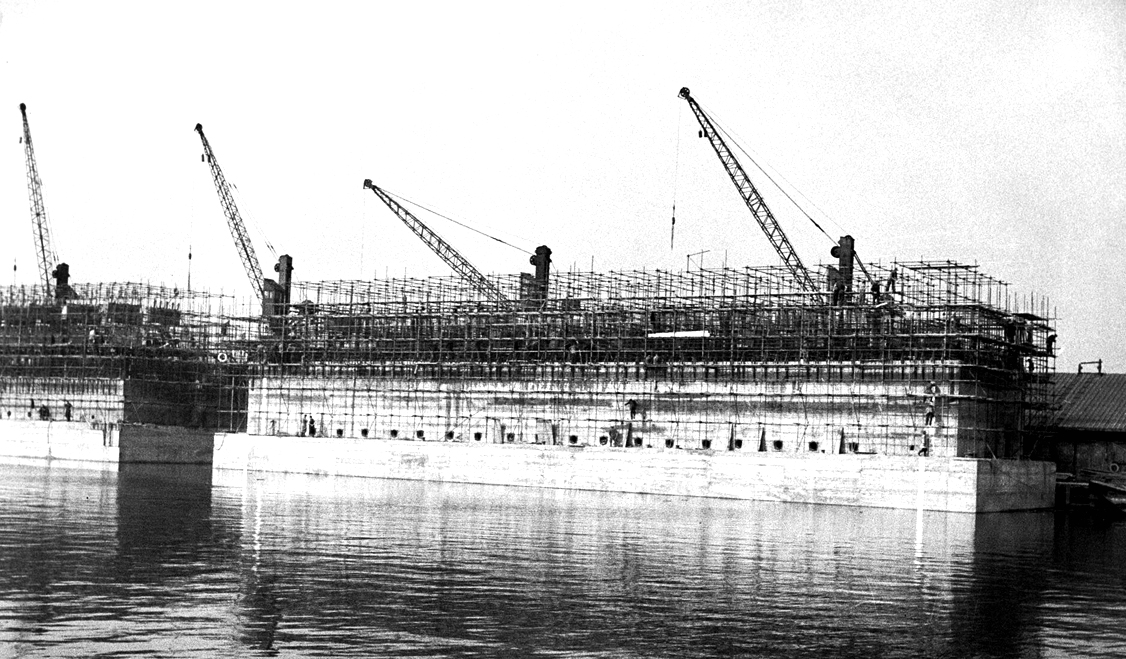

The largest type of Phoenix caisson that the contractors eventually designed was 200 feet long, 60 feet high, and weighed more than 6,000 tons. More than 213 of all types were built, which required more than a million tons of reinforced concrete and 70,000 tons of steel reinforcement. The piers, code-named bombardons, were attached to massive steel pylons that rested on the seabed. In accordance with Churchill’s directive, the piers did indeed “float up and down with the tide”—assisted by an ingenious system of hydraulic jacks. Linking the piers to the land were the floating roadways made up of steel pontoon bridges (the Whales). The floating roadways and Mulberry anchor systems were designed by Lieutenant Allan Beckett of the Royal Engineers. *Image below

Dozens of construction companies and 200,000 workers toiled at London, Tilbury, Woolwich, Barking, Portsmouth, Southampton, Middlesbrough, and other ports all over England to complete the artificial harbors in time for D-Day. In all, the two Mulberries required about two million tons of concrete and prefabricated steel. There were about 623,000 tons of reinforced concrete in 147 caissons. Huge excavations were carved out in the banks of the Thames and Medway Rivers to allow the great Phoenix units to be built, and 200 tugboats were deployed to haul the harbor parts to their moorings. The whole project was estimated to cost 25 million pounds for the eight-month period.

Led by Sir Bruce White, a World War I Army veteran and former harbor builder, the Royal Engineers supervised the construction phases, while the Royal Navy took care of planning, delivery, and assembly operations. Various segments of the Mulberry structures were stockpiled in streams and inlets around the English coast before their assembly, some within range of German long-range guns at Calais, France. This was a deliberate deception to confuse the enemy about the planned invasion route.

The great project went ahead under tight security. The harbors were built in sections ready for towing to the French coast. One of the Mulberries was to be set up off Omaha Beach at St. Laurent-sur-Mer in the U.S. V Corps landing area, and Port Winston was to be assembled at Arromanches in the British-Canadian-Free French sector of the Normandy beaches. Although the concept appeared simple, the execution was complex and required the skills of many engineers to put the harbors in place. That the entire project took only eight months to complete was signal testimony to the capacity of British industry, already stretched to the limit by four years of war.

Secrecy was so stringent that many of the Mulberry component builders did not know what they were working on. When a rumor circulated in the assembly yards that the concrete monoliths were in some way merely destined for the postwar building trade, a senior British officer was sent from Whitehall to reassure the workers that they were in fact doing vital war work. German intelligence did not know what was happening in the southern English ports, although it was certain that the concrete structures must be floating moorings or fuel storage tanks for use in the coming invasion.

Lord Haw Haw (William Joyce), the sardonic-voiced, Brooklyn-born German broadcaster, confidently told British listeners in May 1944, “We know what you’re doing with those caissons. You intend to sink them off the coast when the attack takes place. Well, chaps, we’ve decided to help you. We’ll save you trouble and sink the caissons before you arrive.”

A week before the day of the long-awaited invasion, the blockships were scheduled to sail from Scotland to rendezvous with the rest of the Mulberry components. The invasion would be dependent on the successful functioning of the harbors, but until there was the chance to test one in action, none of the planners, engineers, or builders knew just what their capabilities were. That test would not happen until the Mulberries were actually positioned on the other side of the English Channel.

In the aerial view of a Mulberry harbor, the breakwaters and piers of the artificial Harbor are plainly visible. A fortunate accident to one of the Mulberry units averted what might have been a major disaster for the Allies at Normandy. One of the hulking concrete Phoenixes went aground at the Brambles near the southern English port of Southampton. Engineers started to pump it out in order to refloat it, but discovered that they could not raise it because the pumps were not strong enough. A salvage expert was found, along with additional heavy-duty pumps. Marshaling sufficient tugs powerful enough to pull the giant caissons against the Channel currents proved a major headache for the Royal Navy, but eventually 150 boats were found to be suitable for the crossing and were moved from sites at Portland, Poole, Plymouth, Selsey, and Dungeness.

The tugs were distinguished by a large “M” on their funnels, and their crews took great pride in the designation. The British tugs were to be assisted by U.S. Army towing launches.

Finally, D-Day arrived, and early on the gray, chill morning of Tuesday, June 6, 1944, British, American, Canadian, and Free French assault troops waded ashore on Gold, Juno, Sword, Utah, and Omaha Beaches at Normandy. The Mulberry harbors and associated Gooseberries were ready to play their part in the massive, meticulously planned Allied crusade. Each harbor, built of two million tons of steel and concrete, enclosed an area the size of Dover, two square miles. The first convoy of 45 blockships arrived in the assault area at 12:30 pm on June 7, and the sinking of the vessels was started at once. The rest of the Mulberry harbor sections followed in a round-the-clock effort. Convoys of eight Phoenixes, eight bombardons, four pierheads, 10 Whale roadways, and two miscellaneous units were towed across the choppy Channel by the tug fleet. The planned speed of three and a half knots was increased to four and a half to reduce the turnaround time. Losses of 20 to 25 percent were expected on the crossing, but few units sank, apart from half of a floating roadway. The Mulberries were in use even before they were fully assembled. Almost from the moment that the first Gooseberries settled into the sand, ships were unloading behind them, protected from the Channel waves.

Great skill was required in assembling the two harbors on the Normandy coast. A key blockship had first to be sunk precisely in position. The initial attempt to do this at Mulberry B failed; the tugs at the stern of the first ship, the Alynbank, let go early. As she was settling down more slowly than planned, the tide turned and swung the Alynbank at right angles to the required position. But this turned out for the best because she formed a useful shelter from the west. At Mulberry A, the positioning of blockships went ahead at a faster pace. At the end of the first week, it was decided to plant an extra Phoenix there. But this was undertaken in failing light and falling tide, and the result was a large unit positioned too close to the main harbor entrance.

The objective of the Mulberry harbors was to disembark 3,000 tons of stores a day by D-Day + 4; 7,000 tons of stores and 2,500 vehicles daily by D-Day + 8, and finally 12,000 tons of stores and 2,500 unwaterproofed vehicles a day. Men, vehicles, equipment, and supplies rolled through the two harbors, and within the first two weeks after D-Day, 20 fighting divisions and more than a million men were ashore.

From June 15 to 18, a total of 15,774 British and 18,938 U.S. troops were landed every day, along with an average of 2,000 vehicles and 25,000 tons of stores. The enemy defenders on the Normandy shore were outnumbered locally, but they were still formidable and put up stiff resistance in front of the Allied armies. Reinforcing these men was crucial, but the weather was about to throw a wrench in the works. Channel storms had delayed the invasion by a day, and they were to play havoc again with Allied operations.

On June 16 and 17, the seas became too rough for towing operations, and on the 18th a special effort was made to make up for lost time. Four Phoenix caissons and 23 Whale tows set out from England, but the weather worsened and 11 of the Whales were lost on the way to Normandy. One of the caissons ran aground.

The American Mulberry appeared to be well protected, and on June 18, the day that it opened for business, the weather was fine. But that evening, the barometer began to fall. Next day, the wind and waves increased, and a major Channel gale erupted at 3 am on June 19. By early afternoon, the wind was blowing at 30 knots and whipping up eight-foot breakers that pounded Mulberry A and the incomplete British Mulberry B. The bombardons were designed only to resist winds up to this strength, while the Gooseberries could withstand even less. Mulberry A and the incomplete British Mulberry B began to break up.

Fearing that a further deterioration in the weather might destroy the harbors, British Lt. Col. Raymond Mais, who was in charge of the piers and pierheads, issued emergency orders. Moorings were doubled, ships outside the harbors were moved clear of the breakwaters, and the tugboats were provisioned. Five hundred landing craft rode out the storm inside the Arromanches Mulberry, where the blockships had been strengthened with a row of caissons. Major Ronald Cowan of the Royal Engineers reported that it was a storm “such as had not been seen in the Channel for 80 years—second only to the one that smashed the Spanish Armada in 1588.”

For four days, the winds screamed like a banshee as the great waves crashed into the harbors, damaging pierheads, washing over and sinking pontoons, twisting piers, dragging anchors, and casting landing craft and other vessels adrift. Six caissons were lost, and piers and roadheads were badly mauled. But the main breakwaters held. Royal Engineer bridge parties and British and U.S. Army tug crews struggled valiantly day and night to keep the harbors intact and corral out-of-control craft. Meanwhile, some unloading continued despite the wind and waves. At Arromanches, British sappers managed to offload vital stores and much-needed ammunition, and even on the worst day they landed 800 tons over the piers. During the four-day storm, 7,000 tons of stores were discharged through Port Winston. Some of the men toiled for more than 40 hours without sleep as the storm raged. None of them would ever forget those four days.

The Americans’ harbor was harder hit than Port Winston. The Utah Beach Gooseberry lost several blockships that were torn open, and the Mulberry harbor off St. Laurent was devastated. The breakwaters were overwhelmed by waves, two blockships broke their backs, and only 10 out of 35 Phoenix caissons remained in position. The piers and bombardons were wrecked, and the harbor was eventually abandoned. When the gale finally blew itself out on June 23, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commander of the U.S. 12th Army Group, went down to the beach to see the damage for himself. “I was appalled by the desolation, for it vastly exceeded that on D-Day,” he said.

Port Winston was not much better off. At first light on the day after the storm died, Colonel Mais walked along the battered piers and pierheads, smartly saluting the weary, unshaven soldiers who greeted him. He said nothing, but they understood what he meant and what he felt. Mais reported later, “It was an appalling scene—corpses, smashed equipment, stores strewn everywhere.” Yet, four days after the storm the overall daily discharge at Arromanches had risen to 40,000 tons. The Royal Engineers’ official history reported, “The Allied beaches were a sorry and disheartening sight; hundreds, almost thousands, of craft and small ships—some up to 1,000 tons deadweight—were lying on the beaches at and above the high-water mark in a shambles which had to be seen to be believed; craft were actually piled on top of each other two and three deep.”

The calamity seriously affected the Allied buildup in the Normandy beachhead, and the arrival of men and supplies fell to a fraction of what the daily average had been before the storm. Bradley’s army now had only three days’ supply of ammunition left, and Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army was three divisions behind in its landing schedule.

Yet the buildup went on. In 100 days, 2,500,000 men, 500,000 vehicles, and four million tons of supplies were landed at Port Winston. Although planned to operate for only three months that fateful summer of 1944, Mulberry B was still in use eight months after D-Day. By the end of October 1944, when the Allied armies had broken out into open country—beyond the bocage and the crucible of Caen—and were pressing the Germans eastward through France, 25 percent of the supplies, 20 percent of reinforcements, and 15 percent of vehicles were landed through the Arromanches harbor.

Mulberry A, meanwhile, continued to be used as a sheltered haven without working piers. All materiel was landed by DUKWs (amphibious cargo carriers) and ferries. The rest was either landed on beaches protected by the blockships or went through harbors at Port-en-Bessin, at the junction of the British-U.S. invasion beaches, and Ouistreham at the extreme left of the British sector, and later in the Pas de Calais.

By the end of 1944, Sir Bruce White reported that 220,000 Allied troops and 39,000 assorted vehicles—heavy and medium tanks, tank destroyers, supply trucks, towed artillery, halftracks, Bren gun carriers, personnel and weapons carriers, armored cars, jeeps, mobile workshops, ambulances, and command cars—had landed dryshod in France. He said, “The invasion of Europe, impossible without the artificial harbors, had been accomplished by British engineering skill.” General Eisenhower declared, “Mulberry exceeded our best hopes,” while General Bradley described the project as “one of the most inventive logistical undertakings of the war.”

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, Eisenhower’s trusted, pipe-smoking deputy, concluded, “The whole question of the invasion of Europe might well have turned on the practicability of these artificial harbors,” while the German war production minister, Albert Speer, admitted that the Allies made the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall irrelevant because they bypassed it “by means of a single, brilliant technical device.”

The Normandy invasion was a “brilliant success” that owed much to the Mulberry harbors, as President Roosevelt pointed out. “You know,” he told Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, that was Churchill’s idea. Just one of those brilliant ideas that he had. He has a hundred a day, and about four of them are good. When he was visiting me in Hyde Park, he saw all those boats from the last war tied up in the Hudson River, and he said, “By George, we could take those ships and others like them that are good for nothing, and sink them offshore to protect the landings.” The military and naval authorities were startled out of a year’s growth, but Winnie was right. Great fellow that Churchill, if you can keep up with him.”

Phoenix Caissons under construction in preparation for tow across the channel.

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/d-days-concrete-fleet/