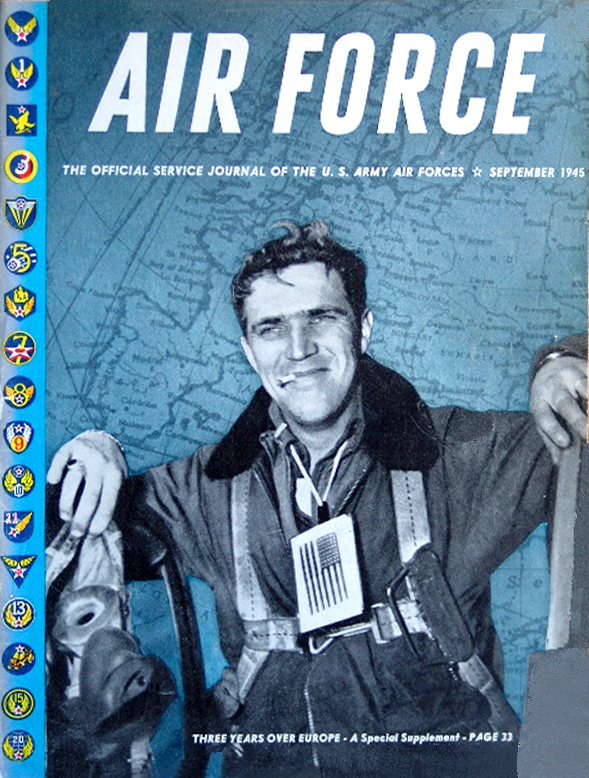

The following article appeared in the September 1945 issue of Air Force magazine, the official service journal of the U.S. Army Air Forces, and discusses in great detail the role played by American airpower in the WW2 European theater. Although the article emphasizes the American contributions to the war effort, it also discusses the actions of all parties, both Allied and Axis, and presents an excellent summary of the role airpower played in the ultimate outcome of the war.

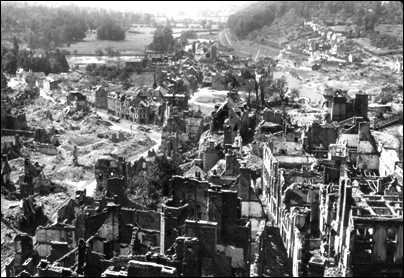

When the Nazis surrendered unconditionally at one minute past midnight on V-E day, May 9, 1945, the gods who love irony must have laughed. Germany, the nation that had first counted on airpower to bridge the perilous gap between its aspirations and its capabilities, then used the air in revolutionary ways to conquer a continent -- there was this nation, shorn of its air strength by superior airpower, its cities beaten into dust and ashes, its industry crippled and driven underground, its armies rendered powerless to halt the march of the invaders.

The Germans themselves were more than willing to admit that airpower had boomeranged on them with terrible impact. In the weeks after V-E day, one top Nazi general after another added his voice to the almost unanimous chorus: "We failed primarily because your airpower robbed our skies of protective wings, our armies of mobility, our tanks of oil and our factories of raw materials." This from the men who had counted on air weapons to lead them to world domination. Irony indeed.

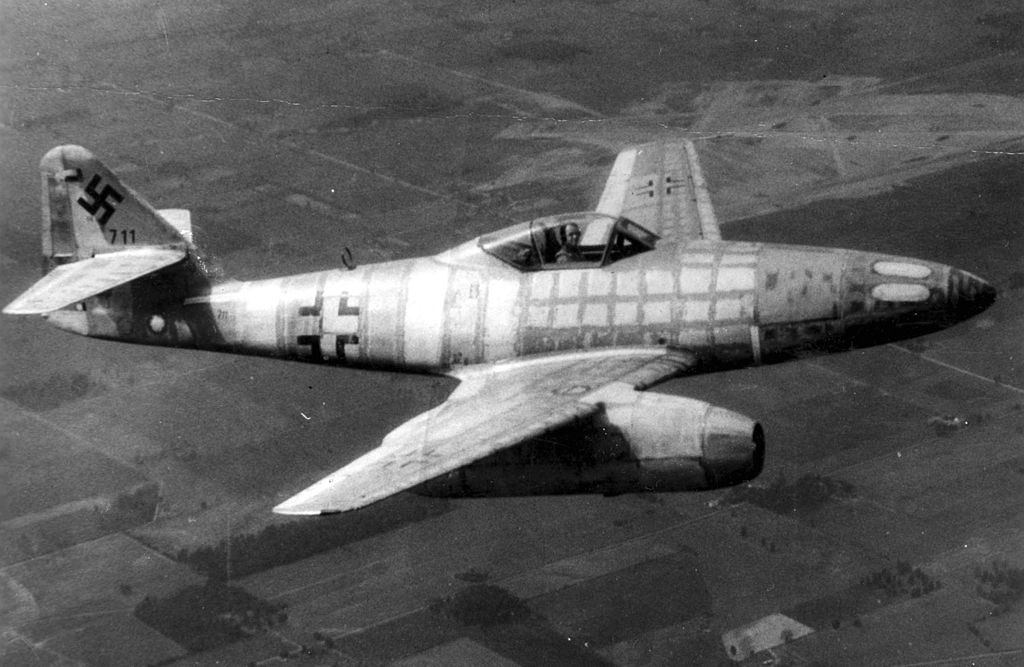

For the laughing gods, however, the irony must have been the sharper for the narrowness of the margin of victory. More than once, even after American strength was thrown into the balance, the Germans nearly won the air war. Given a little more foresight, they might have created a single-engine fighter force that would have halted our air invasion of Europe. Given a little more time, a little more luck, they might have brought their V-weapons and their jet planes to a point where they could have forced a stalemate. But, as one of their airmen remarked bitterly after his capture, their timing was consistently bad -- their critical decisions on how to apply their strength were usually made too soon or too late.

This was most unfortunate for the Germans. It is the application of power, not power itself, that decides battles. Thinking, not sheer masses of planes or tanks or guns, is what wins wars. In the air, where there were few precedents to follow and few textbooks to study, the side with the best brains was bound to win. And it did.

The victory was so enormous that it was hard to grasp at first. To the men of the US Army Air Forces (AAF) who did the flying in the European Theater of Operations (ETO), and to the men on the ground who handled the countless small anonymous tasks that kept the planes aloft, the days immediately after V-E day were touched with a strange unreality. There was both pride and bewilderment in the face of victory. Pride in the magnitude of the achievement, reflected in the price that was paid -- 8,314 heavy bombers lost in combat, 1,623 medium and light bombers, 8,481 fighters, 38,185 men killed or missing. And bewilderment because the scope of the effort seemed so vast as to defy comprehension. "We did it, all right," said one crew chief, "but we'll never know exactly how."

In a way, the crew chief was right. Nobody will ever know exactly how the AAF applied the aerial power without which the war could not have been won. In war, as somebody once said, truth is the first casualty. Not necessarily because sinister forces try to hide it, but because it is so hard to pick out from the mass of irrelevant detail.

The story can be told in outline, however, and the main threads of the narrative are not tangled or confused; they are quite clear.

From the beginning, the mission of Anglo-American airpower was to weaken the German will and means to wage war, to a point where successful landings could be made on the Continent, and then to facilitate the destruction of the German armies by our own. To accomplish this mission, it was necessary to cripple certain key German industries. Before that could be done, it was essential to neutralize the Luftwaffe and retard the development of German counter measures such as the V-weapons that threatened the success of the whole plan. But the broad strategic mission was plain: set the stage for invasion, then facilitate exploitation by the ground forces. Everything that the AAF did was directed to this end, with the comforting knowledge that every blow struck against the Nazis, directly or indirectly, aided the Russians on the gigantic Eastern front.

There was not, it is true, always complete agreement as to the methods by which the defeat of Germany was to be accomplished. We made errors of judgment, which are easily discernible by hindsight. We underestimated German ingenuity in repair and salvage. We may have been too confident about the ability of heavy bombers to protect themselves against improved fighter tactics. We were slow to grasp the full importance of photo reconnaissance -- night photo coverage never was adequately developed. We bit off more than we could chew in the way of target systems -- partly because overall war strategy necessitated diverting heavy bombers to another theater early in the war. The task of neutralizing the V-1 sites was particularly difficult, and the first results left much to be desired, although the net result probably saved London. Our early airborne efforts were not the smooth operations of 1944 and 1945.

But these were just grammatical errors compared with the grievous blunders the Germans committed in their use -- or rather misuse -- of airpower. The Teutonic mind, capable of brilliant short-range planning and revolutionary engineering, seldom showed the imagination and foresight that would have enabled the Nazis to exploit their initial advantages. They failed in the Battle of Britain and in their attempts to blockade the British Isles. They failed in their final defense of the homeland, more because they planned their air defenses too late than because of any material or mechanical deficiency.

This was not true of American planning. In the broad application of airpower, our basic ideas were sound, although in some cases we seemed to be flying straight into the teeth of the best air doctrine. The proof of the pudding was in the eating thereof. The fact that we were eating the pudding less than three years after our recipe went on the stove is one of the most extraordinary military achievements of all time. It is, moreover, a testimonial to our air thinkers, who had been teaching certain basic doctrines in our military schools for 15 years prior to the war.

How those somewhat academic doctrines were tested in the battle laboratories of war is a long story, but if it is ever dull, that is the fault of the storyteller. The individual participant, immersed in his particular task, was in no position to see the air war over Europe as a gigantic chess game in which one move was countered by another, one tactic brought forth another, with the issue actually in doubt until superior power and more intelligent application of that power brought the final checkmate. But it was.

One thing that makes the story fascinating is speculation about what did NOT happen. The might have beens of war are not unprofitable to contemplate, for we may be sure that our enemies of the future will not neglect the study of them. If the Germans had not changed target systems multiple times in the Battle of Britain (from the docks and channel shipping, to the few fields that serviced the Hurricanes and Spitfires, and finally to the bombing of London); if they had moved through Spain to pinch off the Mediterranean at Gibraltar; if we had allowed ourselves to be dissuaded from our determination to carry out daylight precision bombing; if the Germans had developed an adequate sight for their rocket-throwing fighters; if our long-range fighter escort had not appeared exactly when it did; if the V-weapon timetable had not been dislocated and retarded by our bombing -- all these ifs and many others are pregnant with military potentialities. What happened is most significant in the light of what might have happened.

There are a thousand ways to attempt to tell the story of the part airpower played in the European victory. There is the statistical method. But statistics have a way of becoming merely astronomical figures that do not tell the whole story. Besides, they indicate only size, and size was not the deciding factor. The statistics are all on record for those who want them.

The best plan, probably, if the larger picture is not to become blurred with too many details, is to attempt to trace the chronological counterpoint of offense and defense from the beginning -- or even a bit before the beginning -- to the end. Let us, therefore, think back to the uncertain days of 1941, when our country was technically at peace, but when, actually, the hot breath of war was on our necks with the reality of conflict only weeks away.

By July 1941, the international situation in which the United States found itself was so critical that the possibility of a two-ocean war had to be faced and all possible preparations made for such an eventuality. Consequently, the President asked the Secretary of War for a report on our military plans and capabilities. That report undoubtedly played a large part in the discussions that took place when President Theodore Roosevelt met Mr. Winston Churchill on the battleship King George V one month later -- a meeting that resulted in the Atlantic Charter.

The air section of the report faced squarely the fact that there could be no invasion of the Continent of Europe for at least three years (the authors of this estimate were correct almost to the day), and then only if the war against Germany were given priority over a possible conflict with Japan. The broad recommendations of the air chiefs, which in the next 40-odd months were followed with amazing fidelity, called for a concentration of our air effort against Germany's war potential from bases in Britain, with a defensive or holding war in the Far East. The report did not foresee the disasters that were to overtake us in the Pacific, but many of the difficulties of daylight operations over Europe were anticipated. The necessity for more armor and more firepower in our heavy bombers and the need for long-range fighter escort were clearly indicated -- this in the days when we had a grand total of 70 heavy bombers fit for combat and, except for the untried P-38 Lightning fighter, no long-range fighters at all.

There were misconceptions in this pre-war report. There were bound to be. The electrical system of Germany, given highest target priority by our planners, subsequently proved more difficult to defeat than anticipated. So were such communications as canals and marshalling yards, once Germany developed her repair system to such a fine art.

The German transport system did not begin to collapse until mid-1944 -- and then only under the impact of very intensive and sustained bombing. We were too optimistic about our bombing accuracy under combat and European weather conditions. We over-estimated the destructive power of high explosive bombs on certain targets. But the startling thing about the report was the fact that it was based on a concept of air attack that flatly disregarded the lessons of air warfare learned over Europe in the two previous years. It assumed that the backbone of American airpower would be the daylight heavy bomber -- a weapon both sides in Europe had discarded, after bitter experience, as too costly a means of waging war. This must have been forcibly pointed out to Mr. Roosevelt at his August meeting with Mr. Churchill, yet the President had enough faith in his American advisers to go ahead with preparations for such an offensive. Without this faith, the European war might still be in progress right now.

In August 1941, the AAF was hardly ready to engage in global war, but it was not totally unprepared either. In April 1939, an expansion program had been inaugurated providing for 5,500 airplanes. A stepped up training program for aircrews and ground crews had been initiated. Orders for military aircraft from Britain and France had resulted in an expansion of our production facilities. When France fell in 1940, the President had called for production of 50,000 airplanes per year. In 1941, the training program was increased to provide ultimately for an AAF of some 640,000 men. This was not ideal, but it was a far cry from the public indifference and inertia that hampered such expansion during the complacent 1930s. If we had, in 1941, the airpower that AAF commanders had long been asking for, the war would have ended much sooner and countless lives would have been saved.

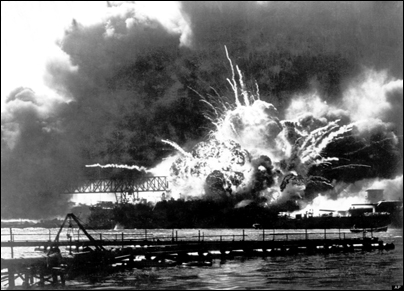

When war finally came the Air Forces were shifting from first to second gear. The foundation for expansion was laid. Yet when the Japanese struck in the Pacific, in December 1941, they virtually wiped out our overseas air arm. And within the continental limits of the United States at the time of Pearl Harbor, there were only 631 airplanes suitable for combat. At right, an unknown battleship exploding. Note also the two heavy gun turrets on the next battleship.

One week after Pearl Harbor, a plan for an Army Air Force of 90,000 planes and 2,900,000 men was complete. Ten weeks later, the vanguard of the 8th Air Force was in Britain. Six months later, in June 1942, a token force of 13 B-24 Liberator heavy bombers flew 2,000 miles from Africa to bomb, by daylight, the oil refineries at Ploesti in Romania. Of these pioneer Liberators, only 4 planes returned to their starting point. The British must have had to bite their tongues to keep from saying "we told you so." The Germans must have relaxed a bit. The real test of daylight bombing was yet to begin.

It did not begin until August 17, 1942, more than eight months after Pearl Harbor. Before discussing this tactically unimportant but historically portentous flight of 12 B-17 Fortresses to Rouen, France, it might be advisable to recall the air situation as it existed in Europe during the summer of 1942.

Of the five air forces that had participated in the European war up to the arrival of the American AAF in 1942, one was extinct, one was a farce, one was a battered enigma, one had won the most important defensive air battle of the war and was building a powerful night striking force, and one -- still the largest and most formidable -- was heavily committed from the Arctic Circle to the Sahara and from the English Channel to the gates of Moscow. (A.A.F. – Army Air Force)

These were the French, Italian, Soviet, British and German air forces, respectively. In the mid-summer of 1942, the four surviving European air forces still showed strong traces of the original thinking that had gone into their composition, although the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and the German Air Force (GAF) were changing rapidly to keep pace with the trends of the war itself. Each of the four had been designed to fit requirements of its own country; each was a mirror, in a sense, of the ambitions and intentions of the people who built it.

Italian airpower, which had looked threatening before the war, with its reasonably good but under-armed fighters, its torpedo and dive bombers, its creditable record in the Schneider Cup races -- and the first publicized jet-propelled flight, for that matter -- had never shown much enthusiasm for real fighting. Its brief appearance in the Battle of Britain had ended in ignominious rout. Its record in Africa was somewhat better, but not much. The Italian Air Force was parceled out to ground commanders and destroyed piece by piece. At best, like the Italian navy, it had maintained a nuisance value, and that was rapidly disappearing.

The Soviet Air Force, virtually destroyed by the German Air Force in the campaign of 1941 and sorely battered again in 1942, had somehow managed to survive -- bolstered by its own reserves and American help -- to the point at least where there was fighter cover for key cities. Within a few weeks, in a struggle reminiscent of the Battle of Britain, this fighter force was to exact a heavy toll on the Nazi Bomber Command's daylight efforts to reduce Stalingrad.

The Soviets had never gone in for long-range bombardment. Perhaps they knew our plans and assumed we would take care of it. In any case, by this time they were pushed too far back for such a program to have made sense, even if they had had the production facilities or the planes.

With much of their industrial area overrun, they were forced to concentrate on types of planes that could give maximum support to their greatest asset -- manpower. One result was the Ilyushin IL-2 Sturmovik (left), a heavily armed fighter-bomber which the Soviets used more or less as a flying tank. An effective ground support weapon, it was not conceived as a match for the best German fighters in aerial combat. Except locally, German air superiority on the huge Eastern front at this stage of the war was complete.

The RAF, at this point, was in a transitional period. Designed as a purely defensive weapon, its primary mission had been to hold the British Isles at all costs, prevent invasion and protect the vital shipping lanes. Fighter Command, aided by radar, German miscalculation and its own magnificent fighting qualities, had won the Battle of Britain -- and with it, time for the Allied nations to set about winning the war. Bomber Command, significantly, had directed its first attack against a Nazi naval base, and up to mid-1942 had dropped most of its tonnage on the German Navy or the bases that supplied it. With the aid of Coastal Command, the two commands had helped avert the threat of invasion. When the Americans first appeared over Europe, Bomber Command was patiently building up its strength in preparation for beginning night attacks over the Continent. It had tried no sustained daylight operations since some disastrous losses in 1939. Like the Germans, it had been forced to fly at night, due to the threat of flak and fighter interception during daytime flights. It was painfully perfecting the pathfinder technique that later resulted in some very accurate night bombing.

The pathfinder technique made use of special advance squadrons that located and marked targets with flares, at which the main bomber force would then aim. But many months of trial and error and bitter losses lay ahead. And between Bomber Command and that perfection still stood the Luftwaffe, with its expanding production facilities turning out a constantly increasing stream of night fighters.

The GAF at that time had about 4,500 first-line aircraft -- a number that remained remarkably constant throughout the war, although the proportion of fighters to bombers increased drastically as time went on. It had already proved itself to be a formidable force. It was, as has been said, the instrument upon which Germany depended to neutralize the overwhelming predominance in size and numbers of the coalition that she knew was bound to rise against her.

In all three cases, significantly, it was the German bomber force, rather the fighter force, that had failed, and each time in the face of determined fighter opposition. Truth was that the GAF had started out primarily as a close support weapon, a sort of flying artillery arm geared to short, intensive ground campaigns, with periods of rest and refitting during winter months. Even reconnaissance was mainly a short-range affair. As such, it had succeeded brilliantly. But it came to the Battle of Britain with no carefully thought-out plan, either of (German Pilots receiving a “Briefing” on the flight line.) blockade, with long-range attacks on shipping and short-range attacks on harbors, or of effective neutralization of the RAF's fighter command.

Actually, it had vacillated between the two, changing target systems from the docks and channel shipping to the few fields that serviced the Hurricanes and Spitfires, and finally, in blind fury, to the senseless blitz of London. Its fighters made the further mistake of flying close to the bombers that they were defending, instead of using broader, area support, so that the British were able to vector their fighters straight to concentrated targets. Apparently German intelligence was not well informed about British radar and how it functioned.

When asked by Allied interrogators after the war why these mistakes had been made, GAF Commander-in-Chief Hermann Goering said that the bombers were so lightly armed that they had to have close fighter support. As for changing target systems, Goering tried to throw the blame for the assault on London upon Hitler, who, he said, ordered it in revenge for the bombing of German cities.

In any case, the Battle of Britain gave the German bombers a jolt from which they never fully recovered. They did good work in the Balkans and paced the panzers into Russia and figured prominently in the battle for Stalingrad. They virtually closed the northern shipping routes to Russia. But they were never able to force a decision at Malta, or chase the British fleet out of the Mediterranean, or even hamstring the endless Russian retreat.

They could and did operate effectively in daylight only in the absence of fighter opposition -- and then their work was more tactical than strategic. The Germans still clung to their concept of the air as a medium for ground support.

When the Americans began their experiment in daylight bombing, the clearest doctrine that had emerged from the air war up to that time was the superiority of the day fighter over the day bomber -- that day bombers would usually lose out when confronted by day fighters.

It had been tested over the beaches at Dunkirk, in the Battle of Britain, in costly RAF assaults on Germany, in the skies over Malta -- and was apparently receiving final confirmation over Stalingrad.

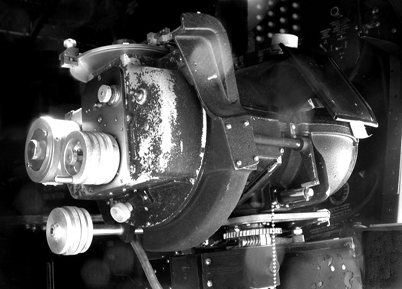

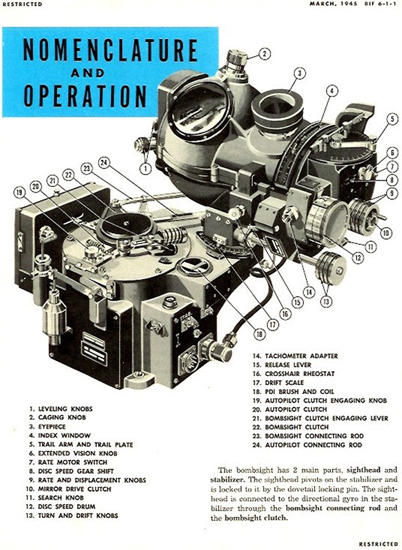

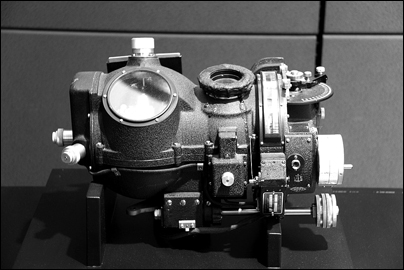

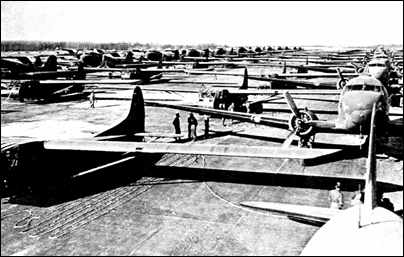

The above thinking was based on the bombers that had been used up to that time -- slow, under-armed instruments of questionable accuracy. But the Americans had two new contributions to make -- a bombsight so accurate that good daylight results were obtainable from an altitude above the level at which flak was effective, and a bomber sufficiently well armed to protect itself against the type of fighters then dominating the skies over Europe. Our B-17s and B-24s, conceived originally as defensive weapons that would enable us to meet an invading fleet far at sea and sink it by precision bombing from above effective flak level, seemed to have the qualifications for successful daylight offensive bombing. And American industry had the capacity for providing the B-17s and B-24s in the necessary quantities.

B-24 (WW2) |

B-17 (courtesy Collings Foundation) |

The British were frankly skeptical of daylight bombing. They had given the matter much thought, and had finally put their faith and national effort into night bombers. They had flown early models of the B-17 over Europe and had lost several. As early as April 1942, they had tested a B-17E and written a report from which they drew several gloomy conclusions. The defensive firepower, they said, was too weak to afford reasonable protection, the tail gun position being cramped and the ball turret very awkward.

They also pointed out that the bomb bay could not carry the huge block-buster bombs (known as "cookies") and that the bomb load was small compared with that of a British Lancaster bomber.

The American reply to this was that improved bombsight accuracy would more than balance the lesser bomb load. As for the armament, certain modifications were being made. Switching from day to night bombing was a vastly more complicated procedure than simply taking off after sunset instead of after sunrise. Furthermore, night technique, at that stage of its development offered little hope of the precision required to take out German factories. And unless this was done, continued production of new planes might make invasion an impossibility.

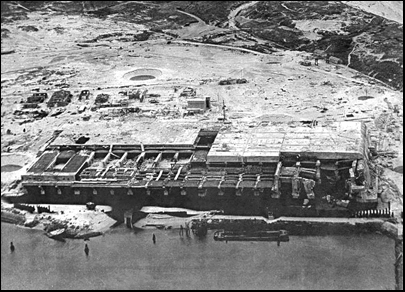

The first Britain-based test of offensive daylight bombing came on August 17, 1942, when 12 B-17s flew during daylight, with Spitfire fighter escort, to Rouen, France, bombed the marshalling yards, and returned without loss. This mission, and the longer unescorted bombing runs of the weeks that followed, were mere military pin-pricks in the thick hide of the Germans, but for anyone who could read the signs, they were among the most important events of the whole war. The question was not whether we were doing serious damage to the submarine pens at St. Nazaire and Brest and Lorient.

Bombed Pens @ Ijmuiden

|

Pens @ St. Nazaire

|

A sub. in Pen at an unknown location

|

German workers repairing sub. at unknown location.

|

The fact is, we were not. The question was whether or not the Luftwaffe could destroy or turn away our unescorted daylight formations from our objectives, as the Spitfires and Hurricanes had either shot down or turned away the Dorniers and the Heinkels from their British targets two years before during the Battle of Britain.

This was the 64-dollar question, because in all the arsenal of democracy, the only weapon that could possibly neutralize the Luftwaffe was American daylight heavy bombing. The Germans did not fully realize this in the autumn of 1942, but the success of the unescorted American heavies did shake their faith -- secure until then -- in a defense based mainly on radar, flak and fighter interception.

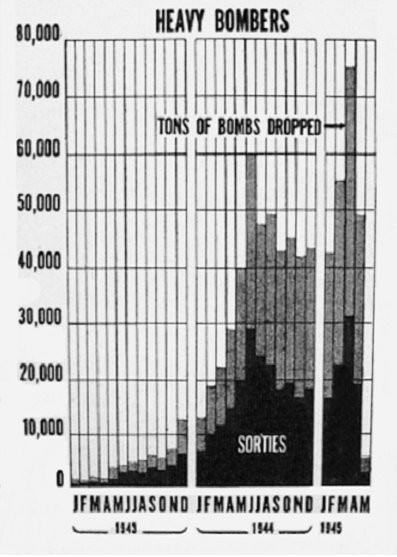

Tonnage Dropped by American Bombers American Bomber Production

|

US Production: As early as the spring of 1942, before an American heavy bomber had even reached an 8th Air Force base in Britain, the German high command had begun shifting aircraft production from bombers to fighters, in preparation for defense against heavy bombers. In December 1941, the U.S. numbers produced had been 510 bombers, 130 fighter-bombers and 360 single-engine fighters. Two years later the figures were 400 bombers, 255 fighter-bombers, and 600 single-engine fighters. By December 1944, single-engine fighter production was 1,425, twin-engine fighters 245, and bombers 15. Sorties: The number of missions flown by American aircraft from Jan. '43 to March '45. |

From the start the Germans developed a healthy respect for the firepower of a formation of B-17 Fortresses. After one laggard, crippled Fort took on a flight of ME-109s over Holland, shooting down two and damaging others, the word went out over the grapevine (we have a German prisoner of war’s word for this) to “lay off those damned Forts.”

But it wasn't long before heavier armament had been installed in the Germans' two basic fighters, the FW-190 and the ME-109, and intensive study of shot-down Fortresses had resulted in improved tactics in attacking bombers.

FW-190

|

ME-109 (1939)

|

ME-109 (1942)

|

Production Numbers for U.S. Fighter Aircraft in World War 2: (fm. WW2 AIRCRAFT.NET)

P-38s- 10,037 P-39s- 9,584 P-40s-13,738 P-47s-15,686 P-51s-15,875 P-63s-3,303

Compared to the sky battles that came later, those early air engagements were small, but they lacked nothing in ferocity, and the caliber of the German pilots was probably higher, on the average, than it ever was again. They were fighting over territory controlled by their own armies; in most cases, the Americans were flying unescorted. If there was ever a time when everything favored the Germans, it was then.

The buildup of our bombers in Britain began slowly. At first we were not prepared to fight every day -- or even as often as weather permitted. If we had tried to, at that time, our loss rate possibly would have exceeded replacement rate so drastically that the whole daylight offensive would have been jeopardized. Knowing this, the commanders carefully conserved their strength.

There are those who claimed that we should have waited until we had sufficient planes to mount a really large offensive, overwhelming German defenses before they could recover from the initial shock of surprise. There are several reasons why this would not have been a good idea. One reason is that we could not have mounted a successful major offensive, even if we had the planes, without the experience gained from trial and error in the early, smaller missions. One of these early battles was fought over Lille, France on October 9, 1942. There was, as might have been expected, an element of confusion. Some squadrons missed rendezvous, some brought their bombs back with them, and there were conflicting claims of the number of enemy fighters destroyed. Such confusion was a necessary preliminary to the cold, almost uncanny efficiency of the operations of 1944 and 1945. We learned that our planes had to be modified in some respects and our training of crews intensified before we were ready for large-scale action. The Germans learned much from our early strikes and improved their defenses accordingly. But we learned far more.

Also, there was no point in waiting for a build-up of bombers in Britain, because the course of the war had dictated a change in overall strategy, which meant that no such build-up could be achieved for several months. That change resulted from the decision to invade Africa.

Operation Torch, as the African invasion was called, was dictated by the activities of a man then known as the "Desert Fox" -- Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. As his panzers (tanks) clanked forward on the dusty coastal road that led to Alexandria, Egypt, the situation in the Mediterranean grew more critical. To those on the Allied side responsible for the conduct of the war, it became increasingly evident that he must be stopped. The worst thorn in Rommel's side was Malta. If Malta fell and Rommel's supply lines grew stronger, then there was every probability that Egypt would fall too. With Egypt would go the Suez Canal and the whole Middle East.

The Germans would flank the Russians, win the Caucasian oil fields, which they so desperately needed, and possibly link up with the Japanese in the Indian Ocean. By July 1942, the consequence of not stopping Rommel (left) were so obvious and so grave that earlier plans had to be shelved. Our Britain-based air offensive would have to struggle along as best it could, without the services of some of its most experienced squadrons and-even more disheartening-without the P-38 Lightning fighter cover originally scheduled to escort the heavy Bombers to targets in Germany.

At the time of 'Torch', American airpower was already represented in Egypt by the 9th Air Force. At the start of the battle of El Alamein, October 23, 1942, it had 164 aircraft consisting of a squadron of B-17 Fortresses, a squadron of B-24 Liberators, two P-40 fighter groups and one B-25 medium bomber group.

These, plus British air strength of some 1,100 planes, were opposed by about 2,000 Axis planes of all types. The Luftwaffe had its hands full dealing with these guardians of Egypt. It could not handle a heavy assault on its rear. The responsibility for that assault was given to the 12th Air Force, which landed with the invasion forces on November 8th.

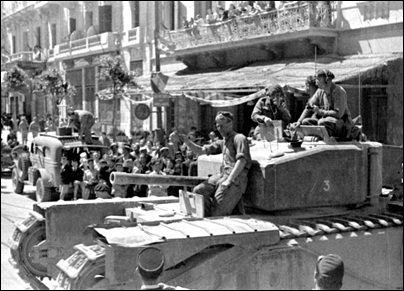

'Torch' differed sharply from subsequent invasions in that it was directed against territory held by a power that was semi-friendly, or at worst only half hostile (the French Vichy forces).

The Vichy were a French puppet government established by the Germans, usually loyal to them, and in control of French colonies in Africa. Adequate air cover, it was thought, could be provided from carriers and nearby Gibraltar. There were two operational plans for the invaders, a war plan in case the Vichy forces resisted, and a peace plan in case they did not. The uncertainty as to which plan would be followed persisted until a few hours before H-hour.

For the invasion, an American paratroop force was flown from Britain in 39 C-47 transport planes in the first American airborne operation of the war. Their story is worth recalling because it indicates the growing pains incident to any new project, in peace or war and because it was the small seed from which grew the great vertical envelopments later in Normandy, in Southern France, in Holland and across the Rhine.

C-47s at the Normandy Landing.

|

WW2 C-47 over Normandy.

|

Boarding a C-47 on the runway.

|

Heading for the drop zone.

|

|

The C-47s took off on the night of November 7, expecting to receive a friendly welcome in daylight the next day. The flight down was a rough one. Most of the planes had been undergoing modification until a matter of hours before take-off. In some planes, wing tip lights burned out, making formation flying in the wretched weather almost impossible. When the planes finally reached Africa, they found severe fighting in progress. French Vichy fighters raked the defenseless transports with machine-gun fire, forcing several to crash-land in the desert. These were some of the difficulties, but even so, the operation had a measure of success, inasmuch as the scattered arrival of the C-47s thoroughly confused the French Vichy air defenses and had them tilting at shadows.

On the whole, air opposition was light. Spitfires from Gibraltar made short work of any Dewoitines (French fighter aircraft) that offered resistance. Carrier-ferried P-40s swooped onto captured airfields. Within a day or two, some heavy bombers, including the "veteran" 97th Group from England, were moved in. Medium bombers and fighters also arrived to begin the long task of hacking at Rommel's rear guards and his supply lines. |

Ready to jump.

|

Loaded deck of a carrier in the Mediterranean.

|

P-40s on the deck of the USS Ranger.

|

Living conditions faced by these airmen were rugged, to put it mildly. Ground crews performed miracles of ingenuity in keeping aircraft operational in a climate that seemed to consist of a diabolical combination of dust storms and bottomless mud. Missions were flown on short notice, with organization improvised on the spot.

Fighter pilots attended bomber briefings to get a picture of the type of mission they were being called on to escort. Troop Carrier dropped the paratroops that captured Bone airdrome, flew countless air supply missions, and learned how to operate on a shoestring.

But even in those early days, the pattern of tactical support was emerging precisely as predicated by the logicians in the pre-war classrooms. First: gain air superiority. Second: isolate the battlefield Third: provide direct cooperation with the ground forces in the liquidation of the enemy. The success of the second phase depended, obviously, on the first. Without air control there could be no interdiction of the battlefield. And until the battlefield was isolated, close cooperation could have no more than local effect. All this the air planners knew already. The African campaign was to teach them how to apply that knowledge successfully.

Air superiority was not gained in a week, or a month. At the time of the African landings, the embryonic 12th Air Force consisted of 551 aircraft. There were 1,700 miles between it and the other jaw of the Anglo-American pincer. And the Luftwaffe fought hard. But the truth was that the GAF, at this moment of its greatest territorial expansion, was simply stretched beyond the limits of its capacity to adequately supply itself. Committed to major efforts in both Russia and Africa, with the growing weight of the RAF's night assaults oppressing its cities and the AAF's Britain-based day offensive already casting an ominous shadow, its doom in Africa was sealed from the moment our landings succeeded. The Germans must have wondered, in bitter afterthought, whether their African squadrons, if pulled out in time, might not have tipped the scale at Stalingrad.

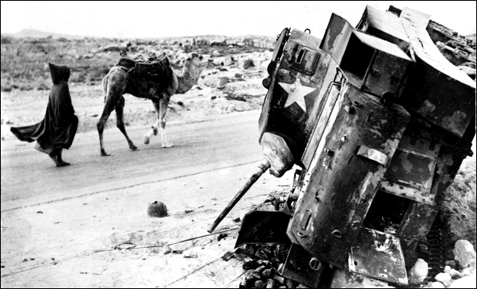

At the time, their faith in Rommel was so high, and the stakes for which he fought so glittering, that any such admission of defeat was out of the question. So they fought on, until the harbors of Tunisia were choked with ships sunk by the AAF, and the desert battlefields were littered with the skeletons of more than 1,000 of their first-line aircraft.

|

|

Images from Tunisia '42-'43

|

While the North African campaign was slogging through the mud that marked the end of 1942, our daylight bomber effort from Britain had reached a virtual standstill. In December, exactly four missions were flown. This was not altogether due to weather, although the weather was bad. It was primarily because we did not have the aircraft available. There were four groups operational in those bleak days -- three B-17 groups and one B-24 group -- and for the moment they were orphans of the war. The requirements of the African campaign were such that expanding our force in Britain was out of the question; its replacement rate barely equaled combat losses, which were mounting as the Germans improved their fighter tactics and as the American heavy bombers moved out of the effective but very short-ranged Spitfire fighter protection.

As for the damage the heavy bombers were doing to their targets – primarily the submarine pens – it did not come up to expectations, to say the least. The concrete pens at Lorient, Brest, and St. Nazaire, with their 12-foot-thick roofs, were protected against any bombs being used at that time.

Furthermore, bombing accuracy under combat was in its early stages. Our bombardiers, who could hit a 100-foot circle from 20,000 feet in the quiet sky over Lake Muroc in California, were only learning how to do the same thing over German-held Europe, with the skies full of flak and hostile fighters.

However, from the point of view of the planners of the daylight offensive, optimism at that stage of the game was not entirely missing. Too much stress had been placed on the limitations of daylight bombing and there had been a lot of publicity focused on its growing pains. Optimism was actually necessary to maintain opposition to critics who, in all honesty, favored the switch of the American air effort to night bombing. Their attitude was based not so much on the belief in the superiority of night bombing as doubt whether day forces could survive fighter opposition. This was the crucial question, and at the time of the Casablanca conference in January 1943, there was no proven answer.

The men who commanded our British-based Fortresses and Liberators, however, were convinced that a switch to night operations would be disastrous. Despite the limited scope of their operations, they had accumulated evidence to document their theories. Some of the evidence was invisible. The diversion of German field armies in Russia and Africa to meet the new air threat from the west, the decline of the GAF bomber forces to meet the demand for fighters -- there were no photographs of these trends, but they existed.

The strain imposed on Germany by a round-the-clock bombing, the opportunity to whittle down the Luftwaffe in daylight combat, the economy of effort inherent in precision bombing -- all these points and others were presented by General Eaker, Commanding General of the 8th Air Force, and hammered home in a long statement to the Combined Chiefs of Staff at Casablanca.

Hindsight shows that the General might have summed up his argument simply by, “Gentlemen, at this stage in the development of night bombing, the destruction of the German Air Force cannot be accomplished by such means. Night bombing will not give us the accuracy necessary to destroy aircraft factories on the ground, nor the opportunity to decimate the Luftwaffe in the air. The only weapon in our arsenal capable of such a task is the American daylight bomber. Unless we use it, and use it soon, the Luftwaffe will be so powerful that a land invasion of the Continent will become an utter impossibility, and even our air invasion will fail.”

The Chiefs of Staff decreed that daylight bombing should continue. They ordered a Combined Bomber Offensive whose mission was "the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system and the undermining of the morale of the German people, to the point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened." That gave the green light to the architects of destruction from high altitude. Ahead of them lay the critical year of 1943. It was clear, even at Casablanca, that the year was to see the most ferocious air fighting in history. The airmen, with other Allied commanders, hoped for a clear cut decision by the end of 1943. The hope for it was well founded but they did not get it.

The reason that more progress was not achieved by the Allies in 1943 was that the GAF still stood between them and their dream of unrestricted bombing of German industry. The Luftwaffe had lost much of its offensive strength, but its fighter production curve was rising steadily and Germany still had faith in the power of an effective fighter force. The world had seen, in the Battle of Britain, what a determined fighter force could do in defending the homeland, even when badly outnumbered.

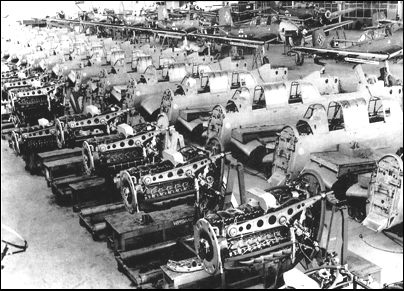

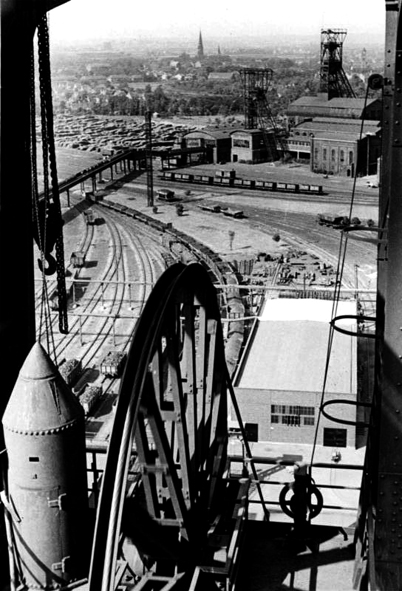

A year before, soon after America's entry into the war, Goering had demanded -- and received -- top priority for the production of fighters. Plans called for production, by December 1944, of 3,000 aircraft per month as compared with the average of some 1,200 per month in 1942. Single-engine fighter production alone was to be quadrupled. The reorganization was planned along mass production lines, with the use of slave labor to overcome manpower shortages as part of the program.

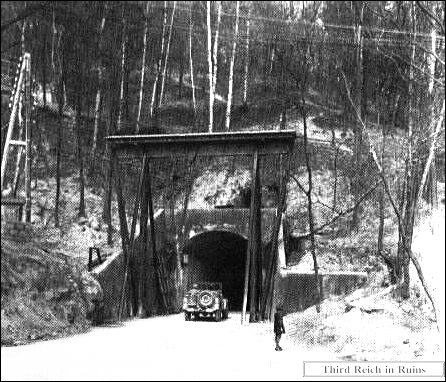

The Germans took the precaution of locating most of their new factories at a respectful distance from the airfields of Britain. They did not think it necessary, at that time, to go in heavily for dispersal or to place their key production centers underground. Nor, apparently, did they reckon with the possibility of air attack from the south on such centers as Regensburg or Wiener Neustadt.

|

|

|

Two Fighter Productions Plants (at unknown locations)

|

|

The result of these miscalculations was a set of industrial complexes ingeniously contrived so that interchangeable units could facilitate repair of any damage to the whole system. It was, at the same time, a concentrated and vulnerable target for any air force that refused to be deterred by distance or aerial opposition. The Germans knew this perfectly well. They had in their possession enough crippled Fortresses and Liberators to know that the same aircraft which could strike their submarine pens on the fringes of Europe had sufficient range to reach the farthest corner of the Reich. But they never dreamed that one day Allied fighters would go all the way with the bombers, and they counted on their own fighter screen to protect the sources of their air strength. Perhaps they even hoped that we would make the effort, and fail, and abandon in despair all plans for the subsequent invasion of Europe.

In any case, in early 1943 the 8th Air Force, with no more than six groups and able to put no more than 100 aircraft over a target, must not have seemed too formidable an antagonist. The Stalingrad disaster and the African situation, where mounting Allied air strength was slowly strangling Rommel, must have caused the German high command more sleepless nights than a certain group of experts working patiently in Britain. But these Operations Analysts were determining, with a cold scientific logic from which the human element was weirdly excluded, which targets represented the Achilles heel of military Germany.

By April they were ready with their answer. The Nazi war effort was based on six major industries: submarines, aircraft, ball bearings, oil, rubber, and military transport. Each industry was vulnerable, to some degree, to high altitude precision attack. Poring over bomb plots and damage assessments from previous 8th Air Force attacks, the experts calculated how many heavy bombers were required to do the job. They weighed the factors of weather, of enemy opposition; they took into account the problems of target recognition, of German ingenuity at camouflage, of such protective devices as smokescreens. Like laboratory technicians, they arrived at a formula calling for certain numbers of planes flying certain numbers of missions. They submitted the plan to the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Give us these tools, they said, and we think we can do the job.

The plan was approved; indeed, the first phase had already begun with an attack, on April 17, 1943, on the Focke Wulf aircraft factory in Bremen. But the loss of 16 heavy bombers in this attack -- the heaviest losses to date -- was a warning that the Germans were not going to let our plan succeed without a bitter and protracted struggle.

Such losses had been expected; the replacement rate had been fixed by the master plan to take care of them. But during 1943, anticipated replacements sometimes did not arrive as originally scheduled, and throughout the best weather months of that year, the 8th Air Force was several hundred planes behind the figure estimated as necessary to do the job. Since the number of German fighters opposing them was steadily mounting, the ferocity of the air battles increased, without decisive effect.

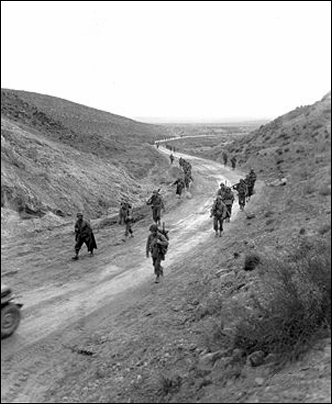

Before tracing the course of the air fighting over Germany in those critical summer months of 1943, it might be well to glance at what was happening in the Mediterranean. There the war was going well. Airpower was slashing at Rommel's over-extended supply line, blocking roads, strafing motor columns, sinking ships, and shooting down air transports. Much of the doctrine of tactical airpower was being reasserted in action: that to operate effectively in conjunction with the ground forces, you first must have control of the air; that when you do have such control, the primary role of tactical airpower consists in attacking supply lines in the rear rather than close support in the immediate battle area.

New lessons were learned every day about the value of softening up the enemy air force by bombing airdromes before launching a ground attack, about the importance of hand-in-glove coordination between air and ground commanders, about the necessity for integrated air forces that could act as a whole rather than scattered squadrons operationally tied to a particular army or navy unit.

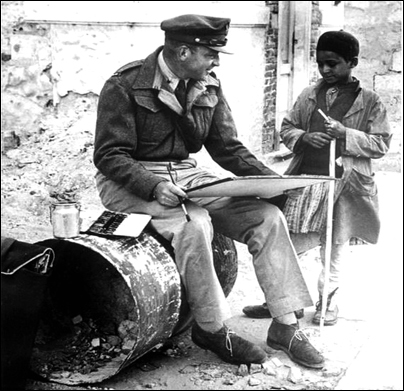

This principle of unity of command was accepted at Casablanca in January 1943. In the following month, the converging 12th and Desert Air Forces were merged into the Northwest African Air Forces under AAF General Spaatz, with a second air command in the Eastern Mediterranean, under RAF Air Marshall Tedder.

General Spaatz Tedder

|

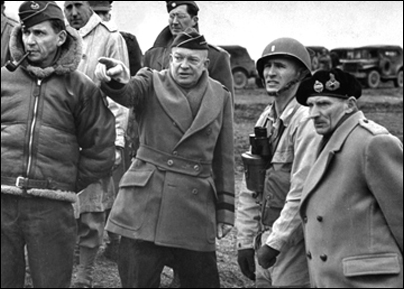

Eisenhower, unknown, Montgomery, Fra. '44

|

It was not until the end of the year that the solution of the joint command problem found clearest expression in the creation of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, in which the function of air units, not their nationality, determined where they were placed and how employed.

As the days lengthened and spring arrived, General Spaatz's forces proceeded with the arduous and necessary task of whittling down the Luftwaffe. A constant problem in those early days was how to find enough fighters to protect the bombers against the still threatening Axis airpower. The original heavy bomber group, the 97th, found revenge for the pounding it had taken from the GAF on its first night in Algiers by plastering Axis shipping and harbor facilities. In December, it had been joined by three squadrons of B-24 Liberators from the 92nd Group in England who lived in the desert on spam and dehydrated cabbage, harassed Rommel's rear guards, and struck across the Mediterranean at Naples and the Sicilian airdromes.

Several medium bomber groups, living under conditions just as rugged, gave the Nazis a foretaste of what B-25 and B-26 medium bombers could do. There were some bad moments in the Tunisian campaign -- as, for example, when Rommel flung his panzers through Kasserine Pass. On that occasion, everything with wings was thrown against him -- even heavy bombers flying below medium altitude. But there were also red-letter days, like the famous Palm Sunday engagement, when P-40 fighters of the 57th Group caught a swarm of JU-52s and ME-323s flying men and supplies to Rommel's hard-pressed forces and shot 79 into the sea in a slaughter reminiscent of the Battle of Britain.

|

|

|

|

Three images from the Kasserine Pass. (WW2)

|

||

In the Mediterranean there was more variety of air combat -- if not more heroism – than was ever dreamed of in northern Europe at that time. High, medium and low-level bombing, bridge-busting, strafing of armored columns and airdromes, skip bombing of Axis shipping -- all these tactics and many others appeared in the 191 days between the Allied landings in North Africa and the collapse of Axis forces there.

It was in this period, too, that an aerial weapon, whose potentialities had never been fully exploited, began to be recognized as an indispensable aid to modern warfare. In 1939, one of Germany's best generals, Werner Von Fritsch, had predicted that the side with the best aerial photo-reconnaissance would win the war. In Britain, the RAF had skilled photo-interpreters assessing bomb damage and making target selections based on high altitude photos brought back by unarmed Spitfires or Mosquitoes. A squadron of American P-38 Lightnings, profiting from RAF experience, was almost operational. But it was in Africa that tactical reconnaissance proved itself invaluable to the ground forces. At one point during the final stages of the drive on Tunis, when weather grounded reconnaissance during the final stages of the drive on operations, the ground commander flatly refused to move until his air photo coverage was obtained.

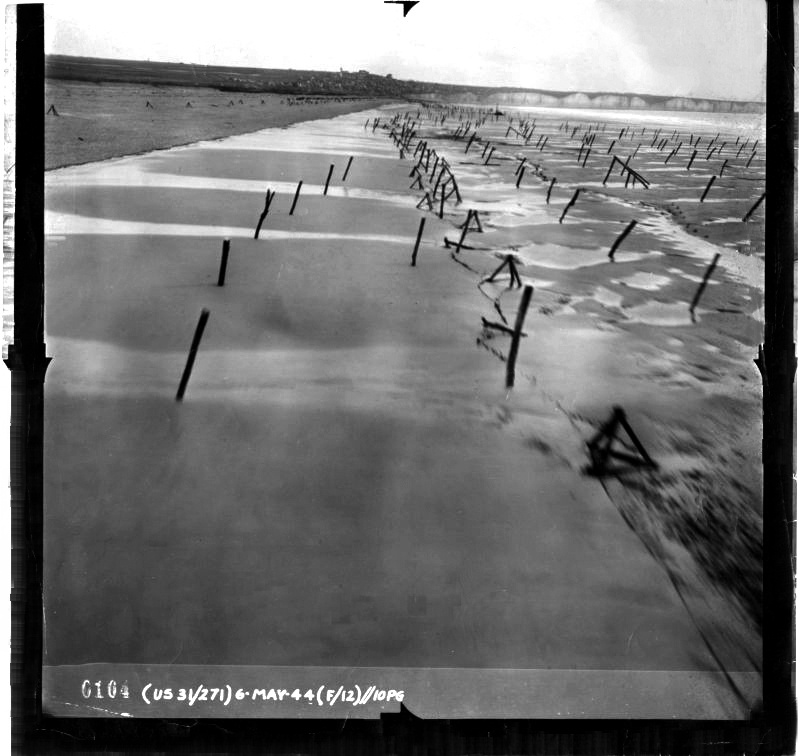

Flying P-38s (F-versions), members of the 90th Photo Recon Wing experimented with night photography, and brought low-level photo-recon missions -- 'dicing' missions, as they were called -- to a state of development which was invaluable later on in Italy and still later they were called -- to a state of development which was invaluable later on in Italy and still later in the battles of France and Germany. They got little recognition for their work -- photo recon was strictly hush-hush in those days -- but they came to be acknowledged as the real eyes of the Army. To the long-range planners, with an eventual D-day in mind, their work proved beyond question that complete photo coverage of the invasion area and its defenses would be indispensable to successful landings.

The following images have be added as examples of “Reconnaissance Imagery” and were not a part Maj. Gordon’s article in 1945. Information has been added about the images and credit given if tagged to the photograph. Images were an important asset (if available) in planning for missions going forward during the war. I have added notes here for the readers in 2020.

Normandy Beach

|

(original)

| |

|

Image was taken 75 feet above the beach on 6 May 1944 probably by a single engine fighter. Note the White Cliffs trailing off to the right. Beach defenses are well in placed at low tide. The image was a single frame on film and remnants of the previous image can be seen at the left edge. Image at left was run through Photoshop here in 2019. | ||

|

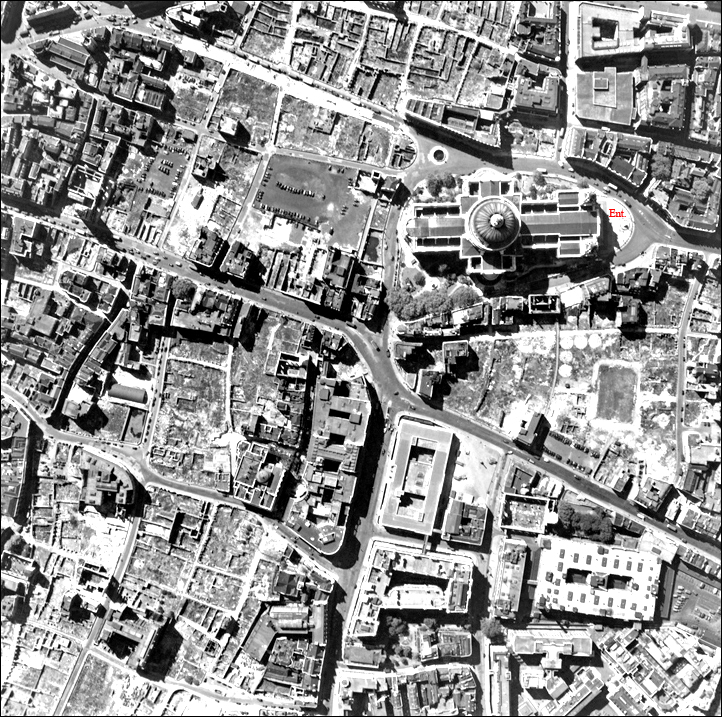

Braunschweig, Germany 10-14-44 The story of the raids on the city of Brunswick, Germany on the night of 14/15 October 1944, will be added at the end of this - Major Gordon's paper in 1945. Eight pages of description will be distilled down with images to further understand the methodology of bombing, reconnaissance and the resulting holocaust that followed on the citizens, property and the lost of life. |

|

The following image has been added to Major Gordon’s work that is again a “Reconnaissance” photograph, but was taken over the City of London and specifically the area surrounding St. Paul’s Anglican Cathedral (below). The German bombing raids on London were quite devastating both in the spread of structural damage to the city, and large fire storms that again resulted in wide spread loss of life in the city.

With the final collapse of the Axis African forces, on May 18, 1943, Allied airpower was free to turn its attention across the Mediterranean to Italy, which Winston Churchill had once called the "soft underbelly" of the Axis. The Northwest African Air Forces was, by this time, battle- hardened aggregation of nearly 4,000 aircraft, with 2,630 American airplanes, 1,076 British planes and 94 French planes. The first Axis target to feel the weight of its blows was the island of Pantelleria.

Between May 30 and June 11, this heavily fortified Italian island in the Strait of Sicily, 62 miles (100 km) southwest of Sicily, rocked under more than 6,000 tons of bombs and finally capitulated without a ground assault -- the first territorial conquest to be achieved solely through airpower. It was a great victory, and a relatively cheap one -- we lost 63 aircraft and claimed 236 of the enemy's while gaining fighter fields indispensable for the invasion of Sicily. But airmen knew that such a complete collapse of a garrison was the exception rather than the rule.

With Pantelleria having fallen, plans moved forward rapidly for the invasion of Sicily. The primary mission of the Northwest African Air Forces was the destruction of the enemy airpower based there. Between July 1 and the invasion, on July 10, nearly 3,000 sorties were directed against airfields on Sicily and on the Italian mainland. The Luftwaffe took such a beating on the ground that it was able to offer only token resistance when the invasion of Sicily finally took place.

YouTube Video – speakers on!

All was not sweetness and light in the air, however, during the invasion of Sicily. The airborne operations, in which American gliders made their first combat appearance, showed with clarity the need for complete coordination of land, sea and air forces.

Training for the airborne operation had been complicated by the weather. Blistering 120-degree F (49-degree C) heat warped some of the CG4A gliders and, just 10 days before the Sicilian invasion, a howling sirocco (wind storm) caused additional damage to the fragile craft. Nevertheless, preparations went forward.

The 51st Troop Carrier Wing, with 133 planes and gliders, was to carry British troops into action, the gliders to be released over the sea but close enough to the coast to make their landing zones. The 52nd Troop Carrier Wing, with 227 aircraft, was to drop American parachutists. Heavy preliminary bombing of the invasion area and strong fighter patrols were ordered.

In spite of such preparations, some things went wrong. Smoke from the bombing, rising to 5,000 feet, blinded both C-47 transport aircraft pilots and glider pilots of the 51st Wing. Defensive flak was heavy.

A strong head wind, plus other factors, resulted in 50 gliders landing in the ocean. The 52nd Wing didn't have much better luck. Some of their craft were shelled by our forces. Fires on the ground, reflecting on windshields, made visibility already obscured by smoke and dust even worse. Eight aircraft went down under fire from both friend and foe. Some chutists landed miles from their intended drop zones. Afterwards, the mission was given an 80 percent efficiency rating, but this charitable reckoning must have taken into consideration the fact that the enemy was thoroughly confused by our own confusion and greatly overestimated the numbers of Allied aircraft involved.

The going continued to be rough for Troop Carrier throughout the remainder of the Sicilian campaign. Not so much from the Luftwaffe -- our strikes against enemy airdromes kept air opposition light. But enemy flak was deadly. On July 11, we lost 23 aircraft out of 144.

Two days later, a misguided Allied convoy sent up a barrage that knocked down seven more C-47s. Harassed pilots began to shy at the sight of anything bigger than a rowboat.

It was a painful process of education, but the lessons were plain and not to be forgotten. They were: absolute necessity for complete coordination between all members of the triphibious team; need for distinctive markings to facilitate aircraft recognition; better radio navigational aids; planes less vulnerable to ground fire than C-47s; bigger drop zones for parachutists. Ruled out of the book were glider releases over water, and the so-called "crash landings" of CG4A gliders, which were too lightly built to stand the shock without injury to the occupants.

These lessons were applied to great advantage a year later at Normandy.

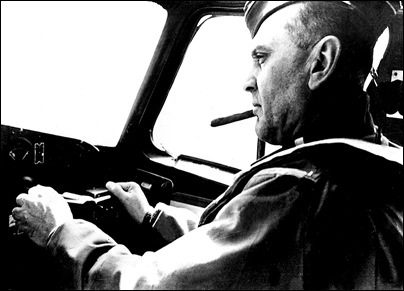

As the Axis grip on Sicily was slowly being broken, five groups of Liberators, three from the 8th Air Force and two from the 9th, staged what was probably the most spectacular single mission of the war -- the August 1, 1943 strike against the Ploesti oil refineries in Romania. The decision to fly the 2,000-mile round trip from Africa and go in at treetop level, gambling heavily on the element of surprise, was a bold one. It was based on the theory that the pinpoint accuracy obtained would justify high losses and that dodging radar detection would minimize losses by catching fighter and flak defenses unprepared.

Unfortunately, some faulty navigation nullified the element of complete surprise. The damage inflicted was considerable, Out of 177 B-24 Liberators, 42 were shot down or crashed, and 31 others failed to return to base. Ploesti was destined to be destroyed eventually by bombing, but to accomplish that destruction, the heavies reverted to their fundamental tactic of high-level precision bombing.

Ploesti Refinery on fire with another group of B-24s approaching. Image probably taken from a previous aircraft. cir. Aug. 1, 1943

|

Low level reconnaissance image perhaps by the tail/belly gunner on B-24. Note the camouflage on oil tanks and walls.

|

B-24 over target at very low altitude as black Images: smoke makes a perfect backdrop.

|

All images Wikipedia, AF.mil., and war birds news.com are from the same raid on the Ploesti Refinery.

|

After Sicily, inevitably, came Italy. Pre-invasion softening up of German airdromes, particularly a spectacular strafing of 200 JU-88s at Foggia, kept the Luftwaffe's head down. But the Wehrmacht was tough. At Salerno, the only suitable invasion point within range of our fighter cover, the Germans drove a counter attack to within a few hundred yards of the beach. Once again, as at Kasserine Pass, the heavies joined the mediums and the fighter bombers in an all-out effort to break up the attack and save the beach-head. On two successive days, more than 1,000 sorties were flown, a commonplace event later in the war, but a distinct achievement over a distant beach-head in September 1943. The morale lift given our ground troops was enormous.

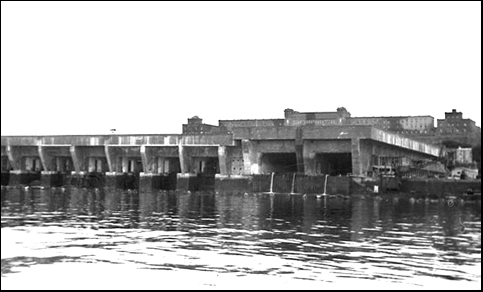

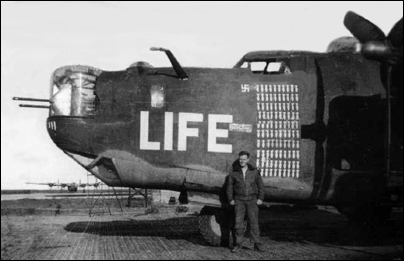

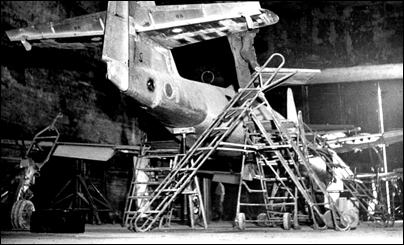

Movement of the 15th Air Force to Italy in the autumn of 1943 was a triumph of logistics. The main objective was to lose as little operational time as possible. Existing airfields in the Foggia area had been badly battered. These were repaired by the Allies and new airfields were carved out of the soggy Italian plain. The engineering problems involved were enormous.

|

|

Marston "Runway" mats being installed in Italy as bases expanded for the Bomb Groups that continued to pour into Italy. A B-24 with "LIFE" nose art inspired by the same magazine at home. Each bomb represents missions flown by the aircraft and crew. |

|

Steel mats (Marston Mats) were essential to keep bombers from bogging down in the spongy turf. Roads had to be built. Distribution of supplies inside Italy was a major headache. Most shipments were landed at Naples, where shattered port facilities were restored with brilliant efficiency by Army engineers. This equipment then had to be transported over the spiny backbone peninsula to eastern air bases. Sometimes the task of moving several hundred tons of steel mat from one side of a marshalling yard to another was more of a problem than getting the same shipment across mountains.

Fortunately, warfare in Africa had taught everyone, including the AAF, much about the difficult art of keeping mobile. Combat crews never once lacked material with which to fight.

Bomb stackage was kept ahead of requirements. Gasoline was piped in and stored in adequate field facilities. By the end of December, supply problems were largely licked. With its strength building up rapidly, the 15th stood ready for the critical responsibilities of the new year.

The year 1943 began with the first tentative strikes by the US AAF against the north German coast. Costly experiments with medium-level daylight bombing had proved conclusively that Nazi flak was too deadly for any but high-level operations. Fortunately, our bombing accuracy had gradually improved to better allow for high-level bombing. Successful high-level attacks on Kiel and Vegesack silenced most of the critics of daylight operations.

In the spring of 1943, however, the cardinal principle of concentration of our air effort was not fully realized. We made some successful strikes against rubber factories at Huls and Hanover, but we were not able to follow up with further such attacks on the factories due to a lack of reserve aircraft, and the Germans were very successful at repairing the factories. Our failure to destroy the rubber industry was an example of biting off more than we could chew.

Besides, we were barely holding our own against the Luftwaffe. By June, the Germans had more than doubled the fighters that opposed our earliest attacks, and had introduced a mortar-type rocket. This rocket out-ranged our .50 caliber machine gun and its burst had a lethal radius of over 100 yards. If the Germans had ever devised an adequate aiming sight for it, they might well have driven us out of the sky before our long-range fighters appeared on the scene. Fortunately for us, P-47 Thunderbolt fighters carrying 100-gallon belly fuel tanks made their appearance in July. They were badly outnumbered, at first, and their range was still limited to the fringes of the Reich. But they slaughtered the twin-engine Nazi rocket-throwing fighters until the Germans were forced into the weird situation of providing fighter cover for their own fighter intercepters.

The range of our fighters, especially when the P-51 Mustangs finally got into action later in the war, was the biggest surprise of the war to most of the Luftwaffe commanders. One prisoner, captured shortly after the Battle of the Bulge, told with evident satisfaction of how General Galland, the Nazi fighter commander, refused to believe the reports of his own men about the long range of our fighter aircraft until four Mustangs pounced on him one day while he was observing an air battle in an ME-410, and chased him all the way to Berlin.

After that he was convinced. So was the German high command. They knew then, as they admitted afterwards, that they had to develop their jet fighters -- and soon. Nothing else would stop the daylight invaders.

All through 1943, weapon clashed with counter-weapon. The Germans tried various forms of air-to-air bombing. None was successful. We trotted out the YB-40, a heavily armed B-17 Fortress designed to be a platform for firepower and nothing else. It was not a success, because the added firepower did not compensate for loss of speed. With better luck, we introduced flak suits that reduced casualties appreciably. The Germans experimented with intruder Fortresses that they had captured, with faked radio signals. We sent a squadron of B-17s to fly some night missions at very high altitude, while the RAF bombed the same target several thousand feet below. The reports were discouraging. Meanwhile, the RAF's superb air-sea rescue service reached the point where it could, and did, drop whole motor launches to ditched airmen, complete with everything except blondes.

RAF's Bomber Command, meantime, was locked in a night duel with the Luftwaffe as deadly as the day conflict between the Luftwaffe and the AAF. Beginning in March, 1943, with a 12-city blitz on the Ruhr, the RAF poured a steadily increasing bomb tonnage on Germany. How much it hurt the Nazis could be judged by the skill and determination with which their night fighter force fought back. It was tough going, and the night bombers could not count -- as the day bombers now could -- on squadrons of friendly long-range fighters to come charging to the rescue. They had to rely on deception and raw courage. They had an abundance of the latter, but the losses were cruel, and German civilian morale showed no sign of cracking under the rain of fire from the night skies.

It is still too early to attempt finally to evaluate the relative merits of night and day bombing at their respective stages of development in 1943. When asked a question along such lines after the war, Goering shrugged his massive shoulders and said, "Well, we could always evacuate the cities!" But it must be remembered that the RAF's pathfinder technique, in which special advance squadrons located and marked targets with flares at which the main bomber force would then aim, had not reached the degree of perfection it attained later. And the use of radar promises to make some forms of night bombing virtually as accurate as day, before the scientists are through with it.

The shattering daylight battles of the last week of July, when the US 8th. Air Force made its first determined assault on the Nazi aircraft industry, left both sides close to exhaustion. It was at this point that the lack of reserve aircraft was felt most sharply by the AAF. By now it was evident that the growth of the Luftwaffe fighter force had to be stopped. With our heavy bomber squadrons weary and below strength, and without long-range fighters for the last stages of deep penetration missions, the planners of the daylight offensive had to choose a target that would cause Germany the greatest possible dislocation. They chose ball-bearings.

Concentrated in a few well-defended areas such as Schweinfurt, the ball-bearing industry looked like the most promising Nazi industrial bottleneck in the late summer of 1943. Its destruction would affect not only aircraft production, but transportation, guns, tanks, ships and many other war products, all of which required ball-bearings for their manufacture and use.

The two deadly air attacks on the ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt, on August 17 and October 14, represented the climax of the major air fighting in 1943. The second attack, which resulted in 59 heavy bombers being shot down over Europe, one in the English Channel, and six that crashed trying to land, gave us proof that until we had adequate Mustang fighter cover over remote targets, the cost was simply too high.

The attacks on the ball-bearing plants produced some of the fiercest air battles of the war. By September 1944, the Germans had lost the equivalent of five months pre-attack war production.

We have the testimony of the general manager of Junkers in Italy that "the attacks on the ball-bearing industry were an unqualified success and disorganized Germany's entire war production." Luftwaffe prisoners, too, complained of engine failures caused by inferior bearings. It is true, however, that Germany was cushioned against the blows to some extent by fairly large reserves of bearings and by the fact that demand for bearings dropped sharply as Allied airpower smashed factories and curtailed production of items requiring bearings. The campaign against the ball-bearing industry hurt the Germans, but it was not decisive in the sense that the later campaign against oil was decisive.

Yet if we were gloomy, the Germans were near despair. Goering issued an order in which he stated flatly that the Luftwaffe's defensive efforts were inadequate. This was significant because the Germans had made frantic efforts to improve it. Steadily increasing attacks by our Britain-based B-26 Marauders on German fighter fields were driving the Luftwaffe farther and farther back toward the territorial borders of the Reich. During August, the Nazis had pulled the crack 3rd Fighter Wing out of Russia -- at a time, too, when the German lines were sagging under the Soviet offensive between Kursk and Orel. They had converted night fighters into rocket-throwing fighter-bombers. They had set up elaborate refueling and rearming points from which their fighters could fly double sorties against the daylight invaders. They had issued orders on pain of court-martial, that German fighter pilots were to go for the bombers and ignore the escort fighters altogether. In a final desperate measure, they had created the Sturmstaffel, a suicidal group of pilots who took an oath to ram the American heavies if all else failed. This Teutonic form of the Japanese Kamikaze never came to much. But the fact that it had official sanction shows the German dread of our remorseless application of precision bombing.

With autumn came bad weather. Our formations had to fall back on instrument bombing, which at that point was far from a state of perfection. The Luftwaffe, licking its own wounds, rarely bothered to come up to oppose our planes.

The climb through the icy overcast wasn't worth the risk involved. Slowly, both sides built up strength for the final test which lay ahead. When USSTAF (United States Strategic and Tactical Air Forces) was created at the turn of the year, with the 8th Air Force almost at full strength and the 15th Air Force building up rapidly in its newly acquired Italian bases, everyone knew the test was at hand. The decisive battles had not been fought in 1943. Perhaps 1944 would be a different story.

The year 1944 began with a furious assault on the German fighter factories. By now there was absolute clarity of purpose as to the first priority of daylight strategic bombing. It was the neutralization of the Luftwaffe. Without achieving that, the great machinery of the D-day invasion, for which the dynamic code word 'Overlord' had been coined, could not begin to turn.

By this time the Germans' monthly production of single-engine fighters had reached 650, with great expansion imminent. Breaking the back of this production would not only safeguard the invasion armada, it would leave our heavy bombers free to attack the real Achilles heel of the Nazi war effort -- oil.

It might, moreover, liberate the RAF from the night bombing that had been its chosen element for so long. Failure to neutralize the Luftwaffe simply meant that the war might be prolonged indefinitely.

The first round was fought on January 11, 1944, when some 800 heavies, with escorting fighters, attacked aircraft factories at Oschersleben, Brunswick, Halberstadt and elsewhere. The Luftwaffe offered furious resistance. Fifty-three bombers and five escorting fighters were lost. Our returning airmen claimed 292 Nazi fighters destroyed.

The decisive attacks came in February, with an almost miraculous week of good weather and a great two-pronged blitz, from Britain and the Mediterranean, on the Nazi fighter complexes. When the smoke cleared away, German single-engine fighter production was reduced by 60 percent, and twin-engine production was cut by 80 percent.

With their amazing antlike persistence, the Nazis immediately started to repair their factories. Constant policing of their production remained necessary, and grew more and more difficult as the industry disappeared underground. But the air losses they suffered during the February attacks, both in planes and in pilots, made it impossible for them to come back to the strength required to defend against the looming certainty of D-day. In succeeding months, the Luftwaffe fought only to protect such vital targets as oil refineries, or the sacred heart of the Reich -- Berlin. D-day found Germany tired and dispirited. The lifeblood had been drained out of it in February 1944.

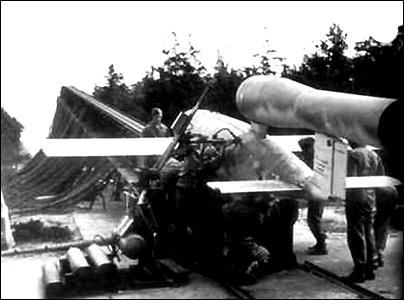

V1 Buzz Bomb that never reached London

|

Remains of a V1 engine

|

V1 is ready for launch

|

Barrage Balloons over the Palace

|

Firemen working through out the night

|

The Morning After a Bombing

|

Siblings waiting in front of their home

|

Back to work in the morning

|

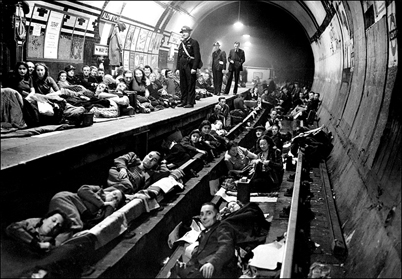

Aldwych Station at night during the Blitz.

|

London in flames with the tower Bridge.

|

Firemen fighting the “Good Fight”

|

Also in February, the German Bomber Command showed a flickering spark of life.

This took the form of a baby blitz on London, an effort in which an attacking force, rarely exceeding 100 planes, took heavy punishment to drop a few more bombs on London, the city that had survived the big blitz of 1940-41, known as the Battle of Britain.

Just why the Germans chose this way to decimate their remaining night bomber squadrons, which might much better have been used against the juicy targets offered by the D-day invasion, still remains a mystery. Perhaps it is not too far fetched to wonder if the German high command, bearing in mind the progress of certain of its secret construction along the French coast, came to the conclusion that their bombers were obsolete in view of what was coming and decided to give German home morale a boost at the cost of their remaining planes. What was coming, of course, was the V-weapon assault on England.

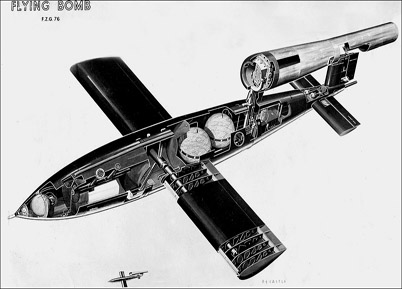

Since the summer of 1943, Allied intelligence had watched, with growing concern, Germany's experiments with a long-range rocket (the V-2) and a flying bomb (the V-1). The RAF's surprise attack on the experimental rocket facility at Pennemunde, on the Baltic coast, was reported to have delayed the work on these weapons by several months. But by the end of 1943, queer launching ramps were mushrooming along the coast, all ominously sighted toward London.

To the B-26 Marauder medium bombers of the 9th Bomber Command went the major responsibility for neutralizing this new threat. The targets became more and more difficult as the Germans modified and camouflaged their launching sites. Moreover, they were so heavily guarded by flak that exasperated AAF crews wondered audibly if the whole thing were not just an elaborate Jerry flak trap. As the concern of high British officials became more acute, heavy bombers were also assigned to the targets. Their use was uneconomical -- fighter bombing in the end was to prove the best antidote to the flying bomb sites -- but the threat was too grave to ignore. The delay imposed on the Germans by the attacks on the rocket sites undoubtedly saved London from an ordeal far worse than eventually materialized.

It is interesting to speculate as to what effect the V-weapon program had on the Luftwaffe. The diversion of materiel – and even more important, of the best scientific brains in the Reich – undoubtedly weakened the Luftwaffe to some degree. The Nazis could hardly be blamed, for they knew they could never hope to match us in mass production of orthodox types of weapons. But if they had concentrated on their jet plane program instead of the V-1, V-2 and other unconventional weapons, they might have realized their dream of an aerial stalemate. In any case, the V-weapon threat never interfered with Allied preparations for the D-day invasion.

A V1 in flight with a chase aircraft within a wingtip distance photo-op, by tipping the wing of the Buzz Bomb w/air pressure, the gyro of the V1 would destabil-ize and crashing the bomb

|

A V2 rocket on its launch pad is being readied for a launch with fuel trucks and personnel about its base. (See HERE)

|

One interesting innovation that appeared in those days was the brief experiment with high altitude fighter-bombing. A P-38 Lightning fighter group, led by a modified P-38 “Droop Snoot” carrying a Norden bombsight and a bombardier, proved capable of dropping a respectable bomb load with considerable accuracy and a minimum of risk. The implications of this type of bombing – with the bomb pattern easily controlled by formation flying, with relatively less danger from flak, with no escort required since the Lightnings could jettison their loads and defend themselves if attacked by enemy aircraft, with a risk element of only one man per ton of bombs instead of two men per ton as in a medium or heavy bomber – the implications were interesting, to put it mildly. Granted that the Lightning was not as stable a bombing platform as a Marauder or a Fortress; granted, too, that the success or failure of the mission depended entirely on the skill of one bombardier in the lead P-38 – nevertheless this method of getting a bomb on a target seemed to have much to recommend it in terms of speed, safety and economy of men and machine.

In Italy, meanwhile, the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces had ably supported the Anzio landings, neutralizing German airfields in the vicinity, and cutting supply routes to the battlefield. But the Germans were able to contain the beachhead and prevent the capture of Rome.

Accordingly, on March 15, an attempt was made to blast a hole in the main front across Italy at Cassino. This was the first mass use of US AAF heavy bombers in close cooperation with ground troops. Four hundred and eighty-three planes dropped 1,205 tons of bombs on the town in a spectacular bombardment that caused worldwide comment. Cassino was pulverized but no break-through was achieved. The ground forces were unable to follow up at once with a heavy infantry attack due to a few hours of waiting for bulldozers to clear a path for tanks through the cratered rubble. In the interval, the stunned Germans were able to regroup and re-establish strong defenses. This lesson was not ignored when similar concentrated bombing was used at St. Lo in France, and at the Rhine and before Cologne in Germany.

In the 12th Air Force's 'Operation Strangle', supply problems of the German armies in Central Italy were made so acute that when the Allies finally jumped off in the push for Rome, German Commander Kesselring was unable to hold them. By cutting all railroads, the medium bombers and fighter-bombers of the 12th forced the Germans to use motor transport. Then the bombers pounced on these motor convoys and destroyed them. When the Nazis, in desperation, tried to send supplies down by sea, Coastal Air Force sank their ships. It was a brilliantly conceived and executed operation.

As the days lengthened, preparations for Operation Overlord (the D-day invasion of France) quickened. Over Europe, Britain-based AAF medium bombers stepped up their attacks on airfields in France and Holland.